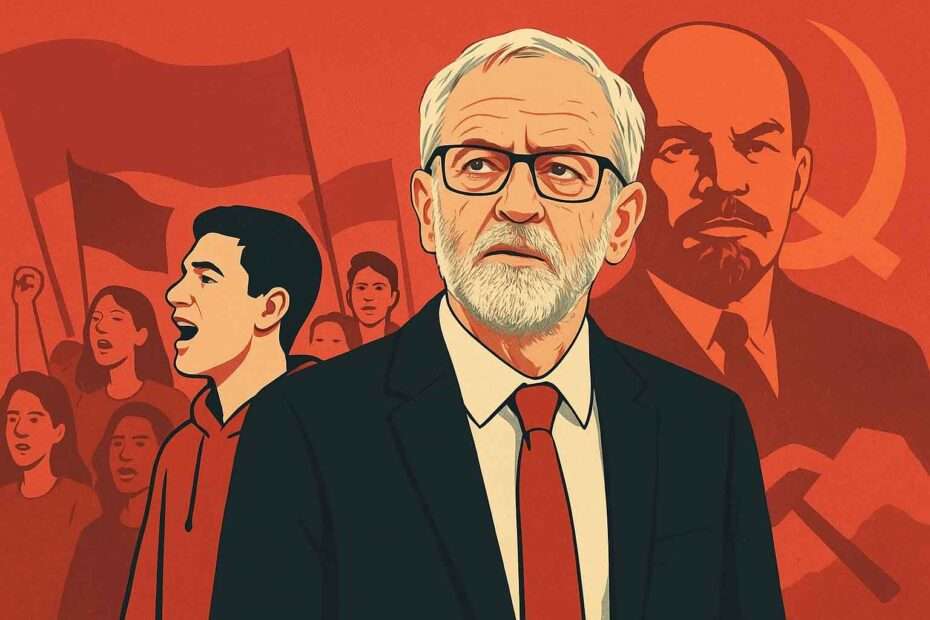

Corbyn’s New Marxist Pitch to the Young

Why We Should Be Concerned

The announcement that Jeremy Corbyn, the former Labour leader, intends to launch a new political movement has not shocked anyone paying attention to British politics. Nor has the revelation that this movement will aim squarely at Britain’s younger electorate, a demographic increasingly disillusioned with the status quo and hungry for something – anything – that resembles an alternative to the current political malaise. What is deeply troubling, however, is the intellectual foundation upon which this project appears to rest, and the extraordinary susceptibility of younger voters to ideological extremism cloaked in the rhetoric of fairness, equality, and idealism.

To the surprise of absolutely no one familiar with Corbyn’s orbit, one of his most trusted former advisers, James Schneider, has suggested that this new entity – operating, for now, under the working title “Your Party” – should look to Vladimir Lenin for inspiration. Yes, Lenin: the architect of the Bolshevik Revolution, the man who seized power in the chaos following Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication in 1917, and the figure who laid the foundations for the world’s first communist state, a regime that ultimately presided over the deaths of millions.

Schneider’s comments were not an offhand joke. He stated quite plainly that Corbyn’s nascent movement should ask itself what “Lenin today” would do if he were leading the fight against Britain’s capitalist establishment. To the casual observer, this may appear as little more than hyperbolic posturing – a bit of revolutionary theatre designed to capture headlines and energise Corbyn’s loyalists. Yet beneath the dramatic invocation of Lenin lies something far more worrying: a recognition that the far-Left sees a unique opportunity to mobilise a generation that has grown weary of liberal democracy, and increasingly receptive to radical alternatives.

The Romance of Revolution Among the Young

For most people over 40, Schneider’s reference to Lenin will have provoked an eye roll. To them, Lenin represents a bygone era, a dusty figure from history textbooks, whose relevance to modern Britain seems negligible. But for a growing number of younger voters – those aged between 18 and 30 – Lenin and what he symbolises carry a certain allure.

Polling conducted recently by the centre-right think tank Onward paints a stark picture:

- 32% of 18- to 24-year-olds in Britain view communism positively.

- Among 25- to 34-year-olds, that figure rises to 40%.

This is not an insignificant fringe; it is a substantial minority of young Britons who see virtue in an ideology responsible for some of the gravest atrocities of the 20th century. Why? The reasons are complex but not inscrutable.

Young people, by their nature, are often starved of idealism in a political culture dominated by managerialism and compromise. They long for boldness, for conviction, for leaders who promise more than tinkering at the edges of the status quo. Liberal democracy, with its slow-moving institutions, its endless trade-offs, and its air of cynical pragmatism, offers little to stir the soul.

By contrast, revolutionary movements promise clarity. They speak of sweeping away the corrupt, the decadent, the unjust. They speak in absolutes – of liberation, equality, and a new dawn. For a generation battered by economic precarity, high rents, insecure jobs, and the sense that life will be worse for them than it was for their parents, the allure of radicalism is undeniable.

Corbyn and his allies understand this perfectly.

Why Schneider’s Lenin Reference Matters

When James Schneider invoked Lenin, it was not simply to signal ideological purity or to indulge in historical cosplay. Lenin was, above all else, a tactician. He understood that revolutions are not spontaneous; they are engineered by small groups of disciplined, highly committed individuals who seize the moment when a state is weakest.

Lenin’s genius – if one can call it that – was his ability to translate ideology into action. He took Marxist theory, abstract and cumbersome, and turned it into a practical blueprint for seizing and consolidating power. His methods were ruthless: the suppression of dissent, the silencing of rivals, the centralisation of authority in the hands of the Party elite. But they worked.

When Schneider says Corbyn’s movement should ask what Lenin would do today, he is not calling explicitly for violent revolution. Yet the implication is clear: study the methods, not just the ideas. Understand how a committed minority can exert disproportionate influence, how narrative and organisation can outmanoeuvre larger, less cohesive forces.

“There have been many communist parties throughout history,” Schneider observed, “which have been formed by 12 or so individuals sitting around a table, which in short order became mass vehicles.”

It is easy to laugh at the idea of a handful of Corbynites plotting over cups of herbal tea and vegan biscuits. Yet history is replete with examples of small, marginal groups that reshaped entire nations. Lenin began as an exile scribbling manifestos in Switzerland. Within months, he was running the world’s first socialist state.

The Democratic Drift: Authoritarian Temptations on Left and Right

The Leninist reference becomes even more alarming when placed alongside recent polling from the Adam Smith Institute, which revealed that:

- 33% of Britons aged 18 to 30 would prefer an authoritarian system led by a strong, decisive leader, even if it meant curtailing some democratic freedoms.

- Only 48% of young people expressed clear support for maintaining our current democratic system.

These numbers should ring alarm bells across the political spectrum. They indicate not only a Leftward drift but a broader disenchantment with democracy itself. When nearly one in three young people is willing to trade freedom for “decisive leadership”, the stage is set for dangerous experiments – whether from the far-Left or the populist Right.

Against this backdrop, the claim that 700,000 people have already signed up to support Corbyn’s new movement becomes deeply significant. This is not a minor protest faction; it is a potential political force, fronted by figures who openly romanticise the strategies of one of history’s most infamous autocrats.

Why the Corbyn Brand Still Resonates

To understand why Corbyn continues to hold sway over a sizeable segment of the population – particularly the young – we must look beyond policy and into the realm of image and emotion.

Corbyn projects an aura of authenticity in a political age defined by spin and triangulation. He is not slick, he is not polished, and to his admirers, that is precisely the point. Where Keir Starmer appears managerial, cautious, and painfully scripted, Corbyn seems principled, passionate, and unafraid to speak uncomfortable truths.

His supporters see him as a benign, almost grandfatherly figure: the man with an allotment, tending marrows, dreaming of a socialist utopia where greed is banished, and fairness reigns. This image – however romanticised – is a powerful antidote to the prevailing cynicism in British politics.

Yet this benign veneer conceals darker affiliations and sympathies. Corbyn’s closest allies have, over the years, expressed solidarity with regimes and movements that are anything but benign:

- Admiration for Russia and its defiance of the West.

- A willingness to excuse or downplay the brutality of Iran’s theocracy.

- A reflexive endorsement of Palestinian groups, regardless of their use of terrorism.

The British far-Left has long harboured these allegiances. In the Cold War era, many were openly sympathetic to the Soviet Union. When that empire collapsed, their loyalties shifted – first to Cuba, then to Venezuela, and increasingly to any state or actor perceived as resisting “Western imperialism”.

This worldview explains why, even now, elements of Corbyn’s camp maintain a perverse admiration for Putin’s mafia state or the Iranian regime. They are seen not as repressive tyrannies but as heroic bulwarks against the capitalist West.

Factionalism: The Hard-Left’s Achilles Heel

If there is a reason to hope that Corbyn’s Leninist experiment will ultimately falter, it lies in the far-Left’s chronic inability to maintain unity. Marxist movements have an almost pathological tendency towards fragmentation. The very obsession with ideological purity that makes them appealing to idealists also renders them incapable of compromise – and compromise is the lifeblood of political longevity.

History provides endless examples: Trotskyists denouncing Stalinists, Maoists splintering from orthodox communists, endless schisms over interpretations of doctrine. Britain’s hard-Left is no exception. Its factions bicker over everything from the legacy of Corbynism to the nuances of intersectionality. It is entirely possible that “Your Party” – or whatever name it eventually adopts – will collapse under the weight of its own contradictions.

Yet we cannot afford complacency. Even short-lived movements can inflict lasting damage on the political landscape. They can radicalise discourse, polarise communities, and undermine confidence in democratic norms.

A Pop Culture Revolution?

Perhaps the most surreal indication of how unserious yet potentially dangerous this movement could be came earlier this week, when independent MP and Corbyn ally Ayoub Khan released a promotional video featuring himself and Jeremy Corbyn shooting hoops to the soundtrack of the film Inception. It was a bizarre spectacle – two men of pensionable age attempting to project youthful energy, set to music from a film about dreams within dreams.

On one level, it was unintentionally comic. On another, it was apt. For the Corbynite project has always been a kind of political dream – a dream of purity, of resistance, of heroic struggle against overwhelming odds. The danger, as with all such dreams, is that it can easily curdle into a nightmare.

Conclusion: The Cost of Forgetting History

The great tragedy of this moment is that so many young people appear unaware – or wilfully ignorant – of what Marxism and its Leninist incarnation wrought upon the world. They see the poetry of revolution, not the prose of dictatorship. They dream of liberation, not of gulags and secret police.

It falls to the rest of us – educators, journalists, politicians of good faith – to ensure that history is neither forgotten nor romanticised. We must remind this generation that the road to utopia, when paved with absolute power, leads invariably to tyranny.

The collapse of trust between voters and the political class is real, and it demands urgent redress. But the answer is not to resurrect ideologies that have already proved disastrous. The answer lies in revitalising liberal democracy, not abandoning it for the false glamour of autocracy – whether of the Left or the Right.

Because if we fail to do so, Corbyn’s movement – and others like it – may yet succeed in turning Britain’s political dreamscape into something far darker.