The Laffer Curve – Lower Taxes results in Higher Revenue

Let’s explore an important economic concept, the Laffer Curve. This concept is named after the economist who developed it, Arthur Laffer, a prominent American economist who has taught at the University of Chicago, the University of Southern California, and elsewhere. The Laffer Curve illustrates two crucial things we need to understand about taxes: how much revenue the government can raise from taxes and at what level of taxation the government might start receiving less, not more, revenue.

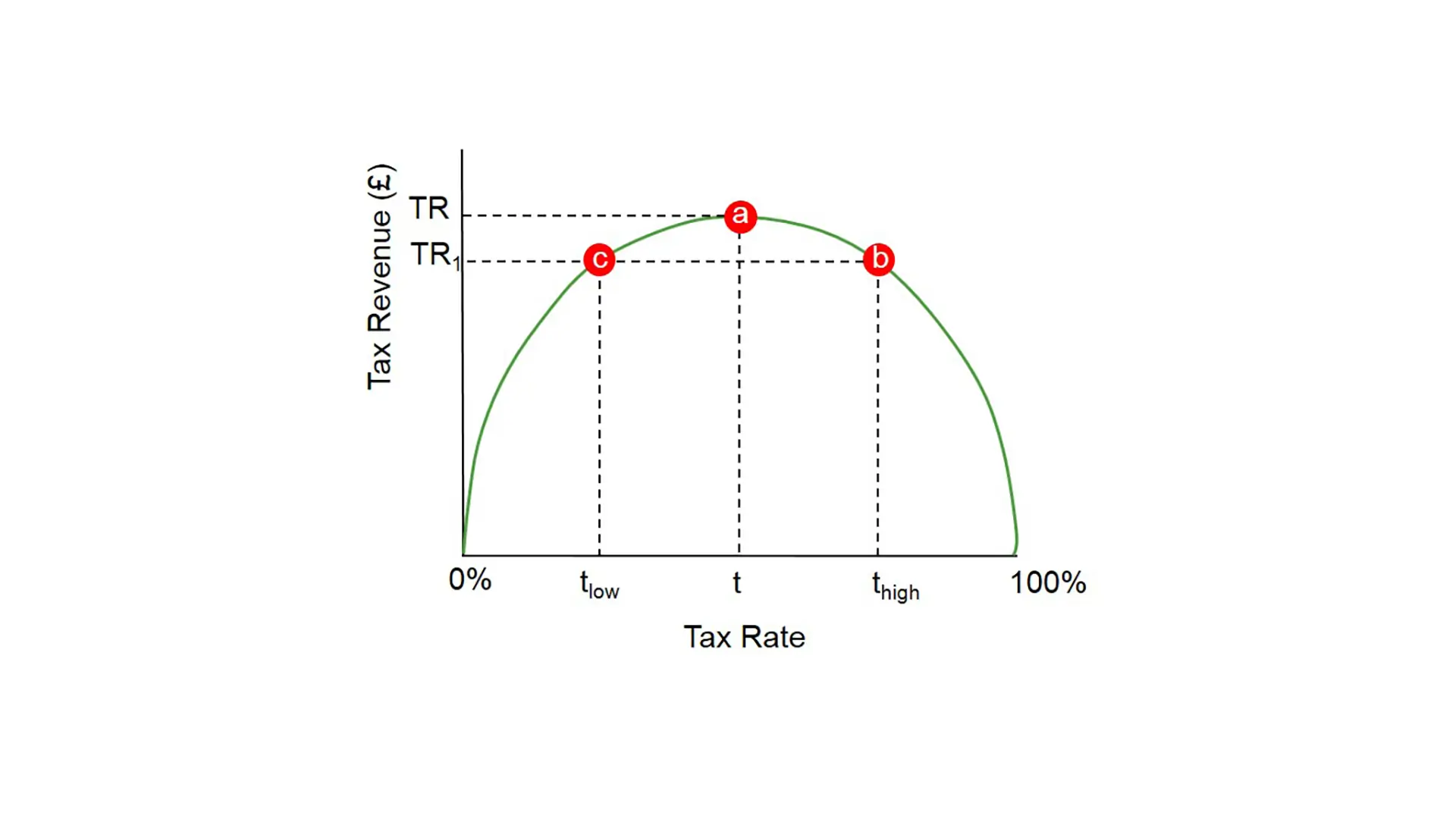

The Laffer Curve is represented by a two-dimensional graph. The horizontal axis is the tax rate that the government chooses, and the vertical axis is the revenue the government receives from that tax rate. First, because zero times any number is zero, if the tax rate is zero, the government receives zero revenue. Accordingly, the point (0,0) is the first point on the curve.

Now, suppose the government chooses a very small tax rate, say 1 percent. The government will then begin to receive some revenue from citizens. This means that another point on the curve must be something like (1,y), where y is a small positive number. If the government charges a 2 percent tax rate, everyone would agree that it will receive even more revenue – which means that another point on the curve must be something like (2,z), where z is a larger positive number than y.

If the government keeps raising the rate, revenue will continue to increase, at least when we’re in the low-tax-rate part of the graph. This means that the curve has an upward slope in this region. However, suppose the government charges a 100% tax rate. In this case, no one would work because the government would take all their earnings. If no one works, the national income will be zero, which means the government revenue will be 100% of zero, or zero. This means that another point on the curve must be (100,0).

Now, when we complete the curve, we see that it must have a hump shape. This is simply because the revenue line has to go up in the low tax rate part of the graph and has to start going down to reach the point we drew at the 100 percent tax rate. If the curve slopes downward, it implies something remarkable – something that few proponents of higher taxes want to admit.

It means that when tax rates are high, if you increase them further, you’ll actually bring in less revenue to the government. This has, in fact, occurred in practice. For instance, during the Great Depression, when Congress passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act, although the act raised taxes on imported goods, the revenue from those taxes actually decreased.

A more recent example occurred in the early 1980s. After President Reagan and Congress drastically reduced tax rates on the rich, the tax revenue from the rich actually increased. All economists – even the most left-wing ones – agree that the true Laffer Curve, the one that reflects real life, has a hump, and that therefore the curve has a downward-sloping part, meaning at some point, tax revenues start going down when you increase rates.

So where do economists disagree? They disagree about exactly where the hump occurs. When I took my first economics class in 1984 at Stanford University, the textbook said that the hump occurs somewhere around the 70% tax rate. But apparently, I was taught something wrong! New evidence from an unexpected source suggests that the hump occurs at a much lower tax rate, something around 33 percent.

That source is a study by Christina Romer and her husband David Romer. Both are economics professors at the University of California, Berkeley. Christina Romer was the chairwoman of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. In other words, the study was written by one of the most influential liberal economists in the United States.

The study was published in the American Economic Review, the most widely respected economics journal in the world. This study examined how national income responds to tax rates. But as far as what concerns us here, the key point is that, if you do the maths, the results imply that the hump on the Laffer Curve occurs where the tax rate is around 33 percent – much lower than economists previously thought.

Let’s now put these findings into political terms. They suggest that, no matter what your politics, you should not want tax rates to be above 33 percent. Obviously, conservatives and many moderates think rates should be lower than that. But even if you are an extreme left-winger and your only goal is to make the government as big as possible, you should still oppose a tax rate higher than 33 percent. The reason is that, as the Romer and Romer study suggests, when tax rates go higher than that, the government actually gets less money.

Everyone, regardless of their political persuasion, should pay attention to the Romer and Romer study and its important implications. They suggest that if we decrease tax rates, government revenues might actually rise.

What is the moral of the story?

The tax rates in the UK were extremely high in the past, in the 1970s, the highest rate of income tax on earned income was 83 per cent. Margaret Thatcher’s government reduced it to 60 per cent in 1980 and 40 per cent in 1989 (equal to the higher rate). From 1989 to 2010, the highest rate of income tax remained at 40 per cent and this was not a live political issue.

As the tax rates began to fall, the revenue that was collected began to rise, but in order for this to be effective over the long term, the government must ensure that the political and economical climate is conducive to commercial investment. The mistake that most governments make with income tax, is two fold:

Firstly, where there has been an economic downturn and the revenue collected begins to fall, the quick-fix, is to raise taxes to plug the gap, now that may work in the first year, maybe even in the second year, but by the third year, investment will fall, people will have less incentive to earn, or expand their businesses and the revenue falls again. Should the government be tempted to plunder the taxpayers once again, which has been done in the past, the downward spiral begins to accelerate and the economy sinks in to serious decline.

However, where leaders have had the courage to reduce taxes, the opposite happens, there is increased investment, growth, income and subsequently more tax revenue, but there is one problem here that leaders face in the modern day, that is the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) which was introduced by George Osborne, to prevent a similar situation that was left by the departing Labour government in 2010.

The problem is, that the OBR has overstepped the mark in recent years, not to mention the fact that it is consistently wrong, in fact, since it was created it has been wrong to the tune of £548 BILLION! it was also responsible for creating the panic in the markets when tax cuts were announced by Kwasi Kwertang in 2022. He along with Liz Truss should have been aware of the risk that the OBR would do this and should not have been so premature with their plans, because as far as the OBR was concerned, these were unfunded tax cuts, but that is because the multiplication factor is not taken in to account by the OBR, which basically means that lower taxes, creates more spending, which generates more revenue and so on. They should have approached this with extreme caution, but as a result of not doing so, the markets went in to freefall and the rest we know.

The other issue is vanity taxes, which is punishing higher earners in order to win favour with the masses, but take this in to account.

10% of taxpayers, pay 60% of all income tax (up from only 35% in 1978)

What would happen if that 10% decided to move their businesses to another country? Even 3 or 4% of them leaving would be catastrophic, but once again, this is a real and present danger.

On top of this, there are many people in what is called “the welfare trap”

They cannot afford to come off benefits, but if they work, they lose so much, that they are effectively working for nothing, and regardless of the ethics, this is the reality, people need incentives and a government that can incentivise the nation will ultimately create a more efficient economy and generate more revenue, which will lessen the burden on everyone, which will in turn, offer further incentive to succeed.

I sometimes wonder if these people understand that a large part of the workforce and even the business world can relocate very easily and lockdown has accelerated this, as more people realised that if they could run their business from home, they could also run it from overseas and not pay these ridiculous tax rates that we have in the UK.