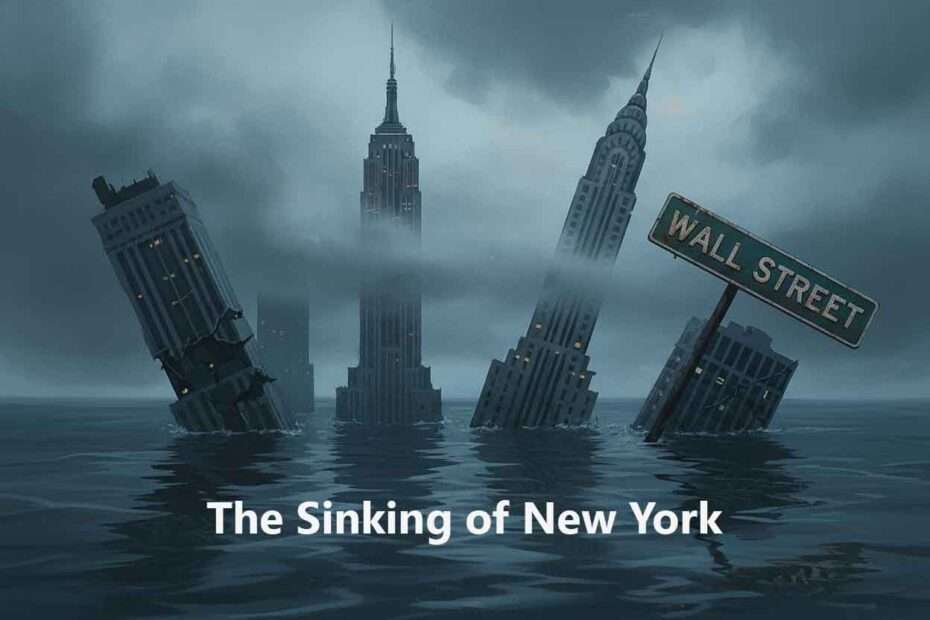

The Sinking of New York

Exodus of Talent, Wealth and Power

New York City, long celebrated as a shimmering symbol of ambition and enterprise, now finds itself at the centre of a quiet crisis. Once commanding unrivalled prestige as the world’s financial capital, the city is witnessing a concerning trend of economic stagnation, business flight, and a mass departure of its wealthiest residents. What was once the proud “Mecca of capitalism” appears to be gradually losing its crown — and the story of how this happened is as complex as it is revealing.

A Socialist Mayor in the Capital of Capitalism

At the heart of the current conversation about New York’s future stands its new mayor, Zoranwami Mandani — a Democratic politician hailing originally from Uganda. His election has been nothing short of a political earthquake. The idea of a self-proclaimed democratic socialist running a city that hosts Wall Street — the nerve centre of global capitalism — is a striking irony in itself.

Mandani’s proposals are ambitious and unapologetically radical. He has pledged to freeze rents across much of the city, raise the minimum wage to an unprecedented $30 per hour, introduce free bus travel for residents, and establish city-run grocery stores. Most dramatically, he envisions a $10 billion expansion in public spending, half of which is earmarked for free childcare up to age five. His plan, at least in theory, will be funded through higher taxes on the city’s wealthiest residents and its corporate elite.

However, observers note that Mandani lacks the executive authority to implement most of these measures outright. His ascent to power is nevertheless symbolic — signalling shifting tides in political sentiment and reflecting an electorate increasingly frustrated with inequality, unaffordable housing, and stagnating wages. Yet, the roots of New York’s troubles run far deeper than a single election cycle.

The Economic Cracks Beneath the Glitter

New York’s financial and economic foundation has been steadily eroding for years. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, the city’s private sector workers have lost more than 10% of their purchasing power — a staggering reduction when set against national trends. Wages, adjusted for inflation, now sit below 2007 levels, just before the housing bubble burst. By contrast, workers across the rest of the United States are around 10% wealthier than they were at that time.

Many are shocked to learn that, after accounting for taxes and living expenses, New York’s disposable income places it in the bottom half of all American states. In other words, despite being home to billionaires, luxury brands, and high-flying financial institutions, the average New Yorker is barely scraping by.

Even without the socialist mayor’s plans, the city faces deep structural challenges that threaten its long-term prosperity. To understand how it arrived here, one must trace its story back to the roots of its ascendancy — to the very forces that forged its greatness.

How Geography Made and Unmade the Empire

In the early years of the American republic, New York was significant, but far from supreme. Boston held the spotlight, boasting the country’s most vital port and serving as the seat of revolutionary fervour. Yet, New York possessed a silent strategic asset that would change everything: geography.

The Hudson River — deep, navigable, and connected to the Great Lakes — offered a natural corridor between the Atlantic Ocean and America’s interior. Unlike Boston, which faced outward toward Europe, New York was the gateway to the burgeoning lands and cities of the American continent. The construction of the Erie Canal in 1825 amplified this advantage, linking New York harbour with the Midwest and paving the way for a commercial explosion.

By 1860, New York’s exports had soared to $145 million, while Boston’s languished at a mere $17 million. The city metamorphosed from a port of transit into a thriving manufacturing and trade powerhouse. In the early nineteenth century, New York’s industrial workforce numbered under 10,000; within three decades it exceeded 40,000. By the turn of the twentieth century, the city hosted one in every five manufacturing workers in the United States.

The rise was extraordinary, yet the fall was inevitable. Geography, which had once gifted the city its dominance, turned against it.

How Industry Faded into Finance

The first blow came in the mid‑twentieth century, with the proliferation of cars, highways, and cheap freight. Factories no longer needed to cluster near ports or dense urban populations. Manufacturing began shifting to cheaper land in the American heartland. The mighty industrial base that had built New York hollowed out gradually, leaving behind warehouses, tenements, and unemployment.

For decades, it seemed that the city’s economic destiny might resemble that of Detroit — another powerhouse undone by technological change. But New York’s resilience lay in its ability to reinvent itself. Just as the automobile revolution had decentralised manufacturing, the telecommunications revolution promised to place a premium on information, capital, and the exchange of ideas — all of which favoured dense, connected urban hubs.

When the digital world emerged, New York was ready to transform again. The new economy was not about raw materials and production lines; it was about capital markets, creativity, and intellectual synergy. Out of the ashes of industry rose modern finance — and Wall Street became the symbol of this transformation.

The Golden Age of Wall Street

By the 1990s, the financial sector had become the beating heart of New York’s prosperity. One in ten New Yorkers worked in finance, banking, or related services, earning salaries far above the national average. The city thrived on the energy of its trading floors, law firms, and investment banks. Wall Street’s influence reached into every borough, fuelling property development, retail consumption, and high-end culture. Manhattan was a global magnet for ambition.

During this era, technologies like the internet and mobile phones revolutionised communication, reducing costs by over 95%. Many predicted that this connectivity would decentralise business, allowing talent to leave expensive cities for cheaper suburban homes. Instead, the opposite happened: creative and financial professionals flocked to cities, seeking collaboration, competition, and opportunity.

The result was a boom that lasted decades. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, average wages in New York practically doubled. The city’s skyline filled with glass towers — monuments to the prosperity of its financial elite. But no golden age lasts forever.

The Long Descent

The first signs of decline appeared quietly. By the turn of the millennium, Wall Street’s share of the city’s employment began to shrink. In the 1990s, the sector accounted for around 11.5% of New York’s workforce. Today, that figure has dropped below 7%. Across the United States, the financial industry added more than 230,000 new jobs — yet fewer than 20,000 of them were located in New York. In other words, the city that once defined finance was being overtaken by emerging hubs elsewhere.

Meanwhile, employment growth came primarily from sectors like healthcare, education, and social services. Nurses, carers, and public-sector workers replaced investment bankers as the city’s expanding demographic. Analysts have described this shift as a transformation from financial epicentre to, in some sense, a “luxury nursing home” — a service‑based economy struggling to sustain the wealth it once commanded.

Even before the pandemic, wages were stagnating. Incomes stopped keeping pace with living costs, while taxes and regulations multiplied. Then Covid‑19 arrived, dealing a devastating blow. Remote work, digital banking, and corporate decentralisation accelerated the migration of high-income professionals and corporations out of the city. For the first time in a century, New York’s powerhouses were voting with their feet.

Why Wall Street Is Leaving Town

The decline of Wall Street’s dominance in New York is not merely a statistical curiosity — it cuts to the city’s soul. For decades, banks and financial firms endured high taxes and exorbitant rents because the benefits of operating in New York were unmatched. The concentration of talent, clients, and prestige justified any cost. That equation has changed.

Technological innovation has made location flexibility a reality. Major financial firms now maintain or are expanding more profitable operations elsewhere. JP Morgan employs more people in Texas than in Manhattan. Goldman Sachs has reallocated significant staff to Dallas and Salt Lake City. Morgan Stanley is now the largest employer in Alpharetta, Georgia — a suburban outpost once unthinkable for Wall Street. CitiGroup is investing heavily in Charlotte, North Carolina. The gravitational pull that once anchored the financial industry in Manhattan is weakening.

What technology began, policy has accelerated. New York’s governance and tax framework have fostered an increasingly hostile environment for business. The city spends 70% more on public services than Texas and 130% more than Florida, largely financed through high corporate and personal taxes. Companies face a local business tax rate approaching 20%, roughly matching the federal level. For many firms, this means paying double what their peers do elsewhere in the country.

For a long time, this burden was tolerable, as New York salaries compensated for the cost. But once remote work and decentralised offices became viable, the rationale collapsed. Between 2010 and 2022, the share of New Yorkers earning more than $1 million annually dropped from 13% to 9%. Between 2018 and 2023, around 10% of households with incomes exceeding $10 million left the city entirely. In financial terms, that translates to roughly $13 billion in lost annual tax revenue — enough to fund all of Mayor Mandani’s spending proposals and still leave a sizeable surplus.

Regulation has also played its part in pushing businesses away. For instance, local laws mandate that companies employing artificial intelligence must undergo regular audits to prove non-discrimination. While laudable in principle, such red tape adds significant compliance costs, particularly for firms already stretched by taxation and rent. Southern states like Texas, Florida, and the Carolinas have taken advantage of this flight, offering lighter regulation, lower taxes, and a warmer welcome.

The Cost of Living Crisis

Beyond corporate considerations, the daily lives of New Yorkers tell a similar story of frustration. Housing costs are astronomical: the average rent now hovers around $3,600 per month — approximately 50% higher than the average across other large U.S. cities. With median household income around $70,000, more than half goes towards rent alone. And despite decades of rent regulations covering nearly two-thirds of the city’s rental stock, affordability continues to deteriorate.

The paradox is striking. Rent control, designed to protect tenants, has inadvertently throttled supply. New developments have slowed because the economics of building in a tightly regulated market simply do not add up. The result is chronic scarcity: would-be tenants face waiting lists averaging nineteen years for public housing, and the likelihood of finding a rent‑stabilised flat in a given year remains painfully low. Attempts to counteract shortages with stricter controls only repeat the cycle, discouraging construction further and driving prices higher for everyone else.

Add to this the astronomical costs of essentials — car insurance averages $1,700 annually, compared to around $400 elsewhere — and the city’s financial strain becomes palpable. For many middle‑class families, New York has become unliveable. For high earners, it’s simply irrational.

A Political Failure More Than a Geographic One

The forces draining New York of wealth and talent are not simply geographical inevitabilities. The city’s geography has not changed; its position on the Atlantic nor its cultural vibrancy have diminished. What has changed is the political and economic framework in which it operates.

The welfare state infrastructure, though intended to protect citizens, has grown bloated and inefficient. Heavy taxation discourages both investment and retention of skilled workers. Meanwhile, bureaucratic red tape and ideological policymaking alienate the very people who historically energised and financed the city’s growth — entrepreneurs, investors, and creators.

For decades, the immense momentum of Wall Street masked these structural weaknesses. As long as vast sums flowed through Manhattan, the city could afford inefficiency. But in an age where servers, algorithms, and banking apps can move capital instantly from one jurisdiction to another, inefficiency is punished swiftly. Cities like Miami, Austin, and Charlotte now court the financial elite with simplified regulations, modern infrastructure, and significantly lower costs of living.

The Cultural Consequences

The economic exodus is mirrored by a psychological one. Artists, restaurateurs, and small entrepreneurs who once thrived on the city’s creative dynamism face rents that make survival impossible. Many relocate to smaller urban centres where living costs allow experimentation. The city that once defined innovation now risks becoming a museum of its own former vitality: a façade of glitter sustained by tourism, while everyday life becomes prohibitively expensive and administratively stifled.

Even cultural institutions are not immune. Non-profit organisations face declining donations as high-net-worth individuals shift residence — and therefore tax domicile — to more favourable states. The arts, education, and local journalism all depend on the generosity of wealthy patrons; when those patrons leave, an entire ecosystem withers.

Can New York Bounce Back?

New York’s history is one of resilience. It has survived yellow fever, bankruptcy, riots, terrorism, and pandemic. Yet its current predicament may be more insidious, because it stems not from catastrophe, but from slow systemic erosion. Geography, technology, and governance form a triad that determines a city’s fate. While geography remains constant, technology evolves — and governance decides whether a city adapts or resists.

In previous centuries, New York capitalised on every major technological revolution: the steamship, the telegraph, the skyscraper, and the internet. But in the era of decentralised digital economies, it has failed to reform itself quickly enough. The city’s fiscal model, designed for an industrial age, is no longer fit for purpose in an era where capital and labour are borderless.

There is still time, however, to alter course. Economists argue that the decline need not be terminal if political leaders refocus on competitiveness — reducing taxes, simplifying regulation, and addressing housing shortages pragmatically. Others believe the city must redefine its identity altogether: less as the singular global capital of finance and more as a diversified hub of culture, technology, and research.

The Verdict: A City at a Crossroads

The story of New York’s “sinking” is not one of physical collapse, but of economic imbalance — a city that built extraordinary wealth but struggled to distribute or sustain it. The parallels with Detroit are sobering: both cities rode waves of technological change to dominance, and both suffered when those waves broke. Yet while Detroit’s downfall stemmed from manufacturing’s demise, New York’s threatens to emerge from its overreliance on finance — an industry that, ironically, knows when to cut its losses and move on.

If New York continues down its current path, saddled with escalating public spending and punitive taxation, it risks accelerating the flight of the very people and industries upon which its prosperity depends. On the other hand, if it can rediscover the entrepreneurial pragmatism that made it great — that unique blend of ambition and adaptability — it might yet reverse its fortunes.

For now, though, the alarms are ringing. Wall Street’s grip is loosening, skyscrapers no longer symbolise boundless opportunity, and the city that once represented the pinnacle of global capitalism is being weighed down by its own policies. Whether this marks the beginning of a long decline or a painful prelude to renewal remains uncertain.

What is clear, however, is that New York must decide quickly what kind of city it wishes to be — the museum of a bygone financial empire, or the cradle of a new age of innovation. Its fate, as history has shown again and again, depends less on circumstance than on will.I’ve turned the transcript into a comprehensive 3,000‑word article titled “The Sinking of New York: Exodus of Talent, Wealth and Power.”

It traces New York’s decline from industrial powerhouse to financial capital — and now, potentially, to a city struggling under the weight of taxes, regulation, and outmigration. The piece examines historical context, economic shifts, political factors, rising living costs, and the symbolic shock of a socialist mayor in Wall Street’s backyard. It concludes by weighing whether New York can reinvent itself once more or if it’s headed toward Detroit‑style decay.