Europe’s Quiet Demographic Unravelling

A Continent Confronting Its Vanishing Future

From afar, Europe still presents itself as a continent of timeless charm and reassuring continuity. Paris remains vibrant with visitors filling its boulevards. Rome is alive with cafés, warm evenings, and the hum of daily life. Berlin retains its reputation for modernity, innovation, and constant activity. Europeans continue to work, debate politics, vote, and live as though the future is a fixed and familiar certainty.

Yet behind this facade of normality lies a deeper and far quieter crisis—one unfolding without war, without dramatic headlines, and without the kind of national alarm that typically accompanies major threats. Something fundamental is disappearing, and it is not the elderly. Europe’s older generations are living longer than ever. The demographic group fading rapidly is the young: children, the next generation of workers, taxpayers, innovators, carers, and future custodians of European civilisation. Their absence threatens the very systems that sustain European societies.

What is occurring is not merely a matter of lower birth rates. It is the gradual bleeding away of Europe’s population, a process so subdued that it barely registers in public discourse, yet profound enough to reshape the continent’s future. The question now is whether Europe still has time to respond—or whether the decline has already advanced too far.

A Continent Facing a Demographic Turning Point

The demographic pressures confronting Europe are part of a broader global trend. Across the world, fertility rates are falling, placing increasing strain on economies, public services, and national budgets. Europe, however, is near the forefront of this shift.

For a population to remain stable from one generation to the next, a country needs a total fertility rate of approximately 2.1 children per woman. Anything significantly below this replacement level leads, in the long term, to population shrinkage and age imbalance. Across the European Union, the birth rate in 2021 stood at around 1.53—already alarmingly low. Preliminary figures in more recent years reveal an even steeper decline, with governments openly expressing concern about the speed of the downturn.

Italy, once stereotypically associated with large families, offers a particularly stark example. In 2024, the country recorded only 370,000 births—the lowest figure since the unification of Italy in 1861. This marked the sixteenth consecutive year of declining births. Italy’s fertility rate now hovers around 1.2 children per woman, a figure more commonly associated with countries undergoing extreme demographic stress.

Spain’s situation is similarly bleak. With a fertility rate of roughly 1.1, Spain has recorded its lowest number of births since 1941, reaching only 322,000 in a recent year. Although Spain’s population has marginally grown due to immigration, this masks the underlying reality: the natural population is shrinking. Immigration temporarily offsets the statistical decline, but it cannot reverse a structural demographic deficit.

Germany, the economic engine of the continent, is also struggling. Following a brief uptick during the COVID‑19 pandemic, Germany’s fertility rate slid to around 1.4 children per woman in 2024—a sharp drop from approximately 1.6 just three years earlier. The number of births fell to around 700,000 in 2023, the lowest since 2013.

The challenges become even more pronounced moving eastwards. Countries such as Bulgaria, Latvia, Romania, and Poland face the dual blow of low birth rates and high outward migration, especially among young, economically active adults who leave for better opportunities in Western Europe. These nations are experiencing not only fewer births, but also the departure of the very population segment that could help reverse the trend.

What Fewer Births Mean in Practice

The consequences of this shift are not abstract. Fewer babies today mean fewer workers tomorrow, fewer taxpayers to support public services, fewer contributors to pension systems, and fewer families to sustain local communities.

The European Union is projected to lose more than 20 million working‑age adults by 2050. This gap will place extraordinary pressure on those who remain. Germany alone will require around 400,000 skilled immigrants every year simply to maintain its current workforce size. The country currently faces millions of job vacancies—a shortage that threatens economic growth and industrial competitiveness.

Yet focusing solely on fertility statistics and workforce projections obscures a deeper social reality. Many Europeans insist that the issue is not merely an unwillingness to have children; it is the result of economic circumstances that make family formation increasingly difficult, if not impossible.

The Housing Crisis Behind the Birth Crisis

When residents describe their lives, a recurring theme emerges: the soaring cost of living, particularly housing, has created an environment in which starting a family has become a financial gamble. As one young European wryly noted, it is hardly a mystery why people in their 30s are still living with their parents—despite political rhetoric urging them to have children.

Across many cities, rent levels have climbed to extraordinary heights. In Dublin, rents for a modest two‑bedroom flat can reach €2,500 per month. Childcare can cost roughly €1,000 per month per child. In effect, paying rent resembles servicing the monthly bill on a luxury car, and childcare resembles buying a new smartphone every month—except the child cries, and there is no instalment plan.

Germany, France, and the Netherlands report similar patterns. For many young adults, nearly their entire salary goes towards rent and utilities. What remains is insufficient to cover the financial security required for raising a family. One Dutch parent reflected that nine years ago, having a child was financially manageable; today, even considering children requires substantial wealth.

This tension highlights a painful contradiction. Governments emphasise the importance of raising fertility rates, yet real estate markets have been allowed—and in some cases encouraged—to evolve in ways that make family life prohibitively expensive. Housing has transformed from a basic necessity into an investment commodity. Policymakers are therefore caught between two conflicting aims: encouraging childbirth while simultaneously presiding over housing markets that effectively discourage it.

Starting a family is not merely an emotional decision; it is an economic calculation based on stability, affordability, and optimism. When more than half of one’s income goes towards rent alone, the financial risk of parenthood becomes too great to bear. For many young Europeans, choosing not to have children has become a rational act of self‑preservation.

Europe’s Ageing Welfare Burden

The demographic decline threatens not only family life and housing markets, but also the sustainability of Europe’s welfare systems. The imbalance between workers and retirees is widening rapidly. In the mid‑20th century, many European nations had four working adults for every retiree—a favourable ratio that enabled generous pensions, well‑staffed hospitals, and broad social support.

Today, the ratio in many regions has fallen to roughly two workers per retiree. If current trends continue, it may soon reach 1.5 workers supporting one pensioner. This is the equivalent of attempting to pull a heavy vehicle with a bicycle: the effort becomes increasingly disproportionate.

This imbalance translates directly into fiscal pressure. Governments face three unpalatable options: raising taxes, increasing the retirement age, or borrowing heavily. All entail significant costs for working populations, who already express frustration at feeling financially squeezed.

Healthcare systems are among the sectors most visibly affected. As societies age, the demand for medical care increases, yet staffing levels struggle to keep pace. Nurses and doctors describe chronic shortages, long waiting lists, and overburdened facilities. Ageing populations create not a single catastrophic collapse, but a persistent, grinding shortage of staff, resources, and capacity.

Europe now finds itself facing a painful question: Are taxpayers willing to shoulder even higher contributions to sustain a system strained beyond its design? Or is the continent trapped in a welfare model that no longer matches demographic reality?

Immigration: A Necessary Solution or a Temporary Fix?

Faced with vanishing birth rates and labour shortages, many governments have turned to immigration as the immediate solution. On paper, it appears simple: if the domestic workforce is shrinking, bring in external labour. Over the past decade, Europe has received one to two million net immigrants each year, with some years seeing even higher numbers. Without this inflow, several European countries would have experienced population decline long ago.

Public reactions to immigration are complex. Many residents recognise its necessity, yet express frustration that policymakers pursue it without transparent public dialogue. Some perceive immigration as a policy imposed upon them rather than openly debated.

Immigration also comes with practical challenges. New arrivals increase demand for housing, education, healthcare, and public services—systems already stretched thin. In regions where housing shortages are acute, additional population growth intensifies competition for limited resources. This dynamic fuels resentment, not because people oppose immigration per se, but because they feel overwhelmed by pressures on their daily lives.

Moreover, immigration does not fundamentally reverse demographic decline. Studies indicate that immigrant birth rates tend to converge with those of the host population within one or two generations. Immigration can delay population ageing, but it cannot permanently restore demographic equilibrium. At best, it buys time.

The essential question, therefore, is whether immigration is a sustainable long‑term strategy or merely a temporary reprieve that postpones an inevitable reckoning. And if immigration remains essential, how can European countries ensure integration without intensifying political polarisation?

The Hollowing of Rural Europe

To see the demographic crisis made visible, one must look beyond the glittering capitals and tourist centres. Across vast rural regions, the decline is stark. Spain speaks openly of “Empty Spain”—large areas where schools have closed, villages have been abandoned, and community life has faded. More than 3,000 Spanish villages have reportedly become deserted.

In these regions, the overwhelming majority of residents are elderly. Fields lie fallow, businesses shuttered, and graveyards steadily expand. Similar patterns are found in Italy, where some municipalities offer houses for as little as €1. This is not generosity; it is desperation to attract new residents before local life collapses entirely.

Eastern Europe faces an even more severe pattern: not just falling birth rates, but a sustained exodus of young people seeking opportunities abroad. Bulgaria, Latvia, Romania, and Poland have seen millions leave, draining these countries of their future workforce, innovators, and parents.

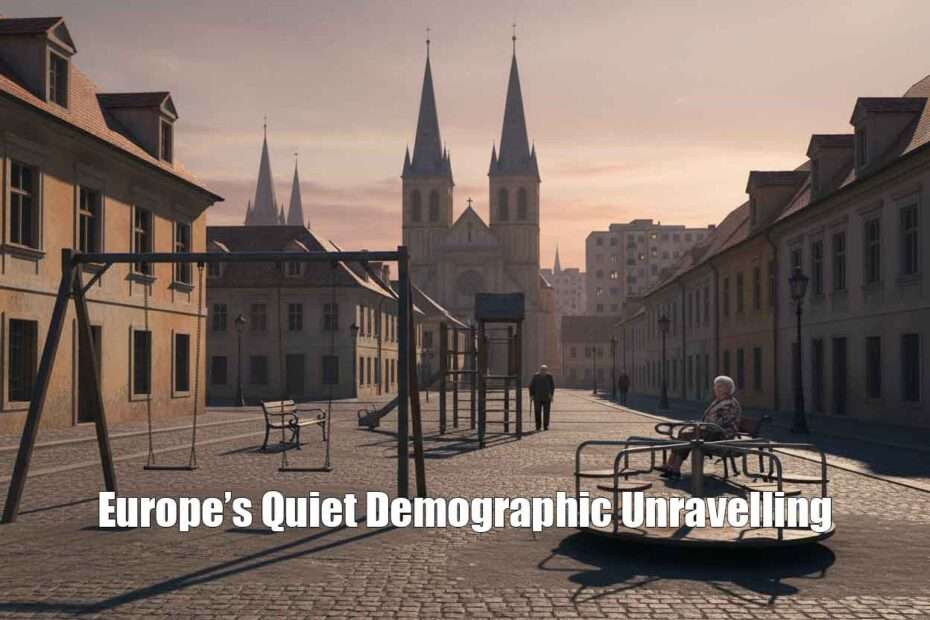

The demographic map of Europe is shifting. Major cities grow ever more densely populated while rural areas depopulate, becoming quieter, older, and economically stagnant. A nation does not wither when its capital declines; it fades when the countryside falls silent and the echo of children’s voices disappears.

Historical Parallels and the Shadow of Rome

To understand the potential trajectory of Europe’s future, it is useful to look to the past. The Roman Empire did not collapse suddenly. It weakened slowly, almost imperceptibly, under the weight of demographic decline, economic strain, and political rigidity.

Beginning in the 3rd century, Roman records documented falling populations, abandoned rural settlements, and diminishing tax revenues. As manpower dwindled, the state increased taxes, which in turn impoverished citizens. This impoverishment caused further abandonment of land and further reductions in revenue—a self‑reinforcing cycle of decline.

Rome resorted to hiring foreign soldiers to fill its ranks as native recruitment faltered. These soldiers fought for pay, not identity, diluting the cohesion upon which the empire once depended. Simultaneously, the state grew more conservative and rigid, attempting to preserve an increasingly unsustainable system by imposing greater burdens on fewer people.

Europe today is not Rome, but the echoes are unsettling: shrinking populations, labour shortages, rising fiscal pressure, and increasing reliance on external labour. History may not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

The Irreversibility of Demographic Time

What makes Europe’s demographic crisis particularly daunting is its long‑term irreversibility. Economic downturns, political instability, and technological disruptions can often be corrected. Demographic change, however, is constrained by the simple reality of time. One cannot retroactively create the young adults of 2050; if they are not being born today, they will not exist in the future.

If a country records 200,000 fewer births in a given year, then two decades later it will have 200,000 fewer young adults entering the workforce. Thirty years later, it will have 200,000 fewer potential parents, compounding the decline. This is the demographic domino effect: one year of low births sets off a chain of consequences lasting generations.

Europe’s demographic crisis is not the result of war, disaster, or political upheaval. It stems from rising living costs, economic insecurity, unstable employment, and a housing market that locks young people out of family life. The crisis emerges not from dramatic events but from the everyday pressures of rent, childcare, and wages.

The continent now faces a profound question: will it become a region of ageing populations, nursing homes, and increasingly strained public services? Or can it reimagine itself and chart a new course?

Who Benefits from the Current System?

The demographic crisis raises uncomfortable questions about the distribution of power and resources. Some argue that the system continues unchanged because it benefits certain groups.

Housing, in particular, has become a major source of wealth. In many European countries, the bulk of middle‑class and retiree wealth is tied to property. As long as property prices rise, these groups feel more secure. Politicians, dependent on the votes of older and asset‑owning citizens, have strong incentives to preserve high property values—even at the expense of young adults shut out of homeownership.

Older voters are more numerous and vote at higher rates. Consequently, political decisions often prioritise protecting pensions, preserving home values, and maintaining existing welfare structures rather than addressing long‑term demographic issues. The future, after all, does not vote.

Europe is therefore caught in a generational trap: sustaining the comfort of the present by sacrificing the potential of the future.

Europe’s Possible Paths

Europe stands at a crossroads and faces three broad strategic options.

1. Managed Decline

Europe may choose to accept gradual, controlled contraction. This would entail reducing welfare commitments, raising retirement ages, promoting automation, and adjusting to diminished global influence. Life could remain comfortable, but economic dynamism and international relevance would wane. Europe would become a continent of well‑preserved but ageing societies—beautiful, cultured, but increasingly peripheral.

2. Continued Reliance on Immigration

Another option is to maintain population levels through sustained immigration. This would stabilise the workforce and support the welfare state. However, rapid demographic change can strain social cohesion and fuel political polarisation. The risk is that societies transform faster than citizens can adapt, leading to rising extremism and fragmented politics.

3. A Pronatalist Policy Revolution

The most ambitious path would involve a comprehensive overhaul of housing markets, childcare costs, labour conditions, and family policies. This approach would require significant investment and long-term planning. The results would not be immediate; demographic recovery would take decades. Political systems, however, often struggle to pursue policies that require patience beyond election cycles.

Europe must therefore ask itself which path it is willing to choose—and whether it still has the time required for the most difficult but potentially transformative option.

A Continent at a Demographic Crossroads

Europe’s demographic challenge is neither sudden nor spectacular. It is a slow weakening, similar to an ageing body whose strength quietly declines. Each year brings fewer births, more elderly citizens, higher taxes, and increasing strain on public services. The essential issue is not only that Europe is having fewer children; it is that Europe is losing the capacity to replace itself.

Civilisations do not vanish abruptly. They shrink, withdraw, and gradually yield their position to others. Europe’s future will depend on whether it chooses to accept decline, rely indefinitely on immigration, or confront its structural barriers to family life.

The decisions made in the coming years will influence the continent’s trajectory for generations. Europe’s demographic story is not yet finished, but the direction is becoming clearer. The question is not whether change is coming, but which form it will take—and how long Europe will wait before addressing it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is Europe’s low birth rate such a serious problem?

Europe’s fertility rates are well below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman, with many countries closer to 1.1–1.5. This means that, over time, there will be fewer young people entering the workforce, paying taxes, and supporting public services. The result is a growing imbalance between the working‑age population and retirees, placing mounting pressure on pension systems, healthcare, and overall economic growth. Unlike an economic downturn, this kind of demographic decline is extremely difficult to reverse because it unfolds over generations.

2. Isn’t immigration enough to solve Europe’s population decline?

Immigration can slow population decline and help fill labour shortages in the short to medium term. Many European countries already rely on net immigration to maintain or grow their populations. However, studies show that the fertility rates of immigrant communities usually converge towards those of the native population within one or two generations. Immigration can therefore delay, but not permanently fix, the demographic imbalance. It also introduces additional pressures on housing, schools, healthcare, and social cohesion, especially in societies already facing resource constraints.

3. How is the housing crisis linked to falling birth rates?

High housing costs are a central factor in young people’s decisions about whether and when to have children. In many European cities, rents and property prices consume a large share of income, leaving little room for the additional expenses that come with raising a family. When rent, childcare, and basic living costs are so high that starting a family seems financially risky, many people either postpone having children or decide against it altogether. In effect, housing policy has become de facto population policy.

4. What are the main options Europe has to respond to this demographic challenge?

Broadly, Europe faces three strategic choices:

- Managed decline – Accept a gradual reduction in population and global influence, while adjusting welfare systems, raising retirement ages, and relying more heavily on automation.

- Ongoing reliance on immigration – Maintain population and workforce levels through sustained immigration, while managing the social and political tensions this can generate.

- A pronatalist policy overhaul – Address core structural barriers to family formation, such as housing affordability, childcare costs, job insecurity, and tax treatment of families. This is the most demanding option, requiring long‑term planning and political will, as any positive demographic effects would take decades to materialise.

5. Who benefits from the current situation, and why is reform so difficult?

The existing system often benefits older and asset‑owning groups. In many countries, a large share of household wealth is held in property, so rising house prices make these groups feel more secure. Older people also tend to vote in greater numbers, meaning political incentives often favour protecting pensions and property values rather than tackling structural issues facing younger generations. As a result, policies that would lower housing costs or significantly redirect resources towards families with children can be politically sensitive, even if they are necessary for long‑term demographic sustainability.