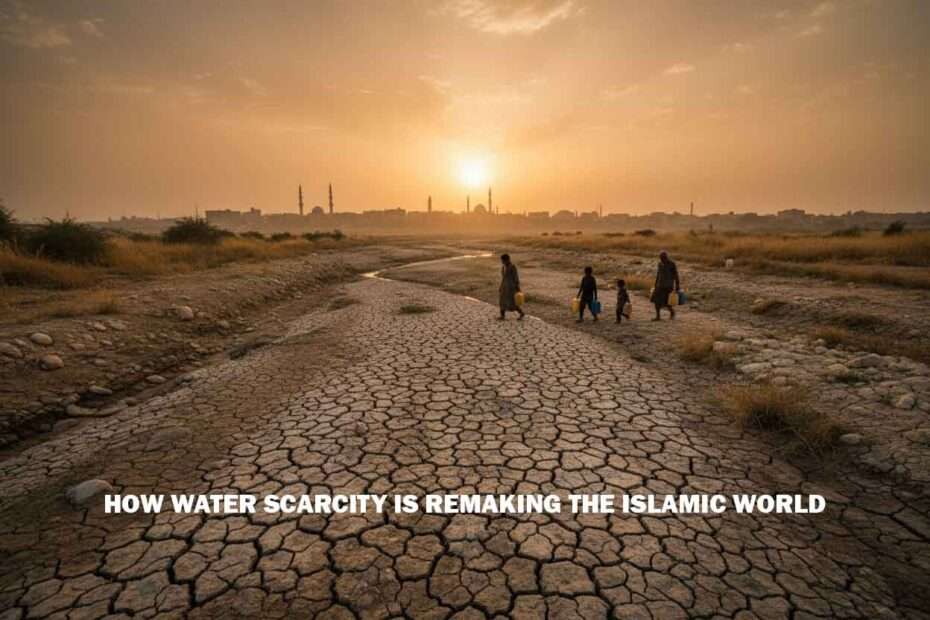

How Water Scarcity Is Remaking the Islamic World

The contemporary crisis facing many Muslim-majority countries is not primarily one of bombs, invasions or competing ideologies. It is something older, more relentless and far less visible day to day: the systematic disappearance of usable water. Rivers are shrinking, lakes are vanishing, aquifers are being emptied, and with them the foundations of societies that have existed for millennia.

From Somalia to Syria, from Iran to Egypt, regions often described as the cradle of civilisation are running out of water. This is not a metaphor. Entire lakes that once sustained ecosystems and economies have effectively disappeared. Mega-cities face intermittent or dry taps. Farmers walk away from land worked by generations. Millions are not fleeing tanks or aircraft, but failed rains, exhausted wells and sterile fields.

This is more than a drought. It is a slow-motion environmental and social unravelling. In a cruel historical irony, the lands where scripture once warned of plagues, famine and divine punishment are now enduring a calamity largely of human making. The present disaster is not an act of God; it is the cumulative outcome of political choices, engineering projects, agricultural policies and global emissions.

The scale and urgency of this crisis across the Islamic world – and more broadly across the Middle East and North Africa – demand careful examination. The numbers are stark, the human stories already tragic, and the trajectory, unless rapidly altered, points towards a century of disruption that could reorder populations and states alike.

The Geography of Extreme Scarcity

One fact captures the severity of the problem: all ten of the driest countries on Earth are Muslim‑majority nations. This is not an incidental feature of the global climate; it is the structural backdrop against which these societies must plan their futures.

Egypt, a country of over 100 million people, tops this list. It receives on average about 18 millimetres of rainfall a year. For comparison, London receives more than 600 millimetres, and New York over 1,200. Egypt survives not on rain, but almost entirely on the Nile.

Libya follows with around 56 millimetres of annual rainfall. Saudi Arabia, though immense in land area, is barely better off. Qatar receives roughly 74 millimetres per year, the United Arab Emirates about 78, and Bahrain only around 83. These are not anomalous desert outposts; they are characteristic of the wider region.

Jordan, Algeria, Mauritania, Kuwait and several others hover around or below 120 millimetres of rain annually. These figures describe entire nations – home to hundreds of millions of people – attempting to maintain modern economies on precipitation totals that in some temperate countries might barely register on annual charts. In effect, vast populations are living on rainfall that would scarcely fill a bathtub.

It is tempting to shrug and say: these are deserts; they have always been dry. Yet this apparent constancy masks a set of profound changes. Historically, societies in the region adapted to scarcity with careful water management, seasonal migration and limits on expansion. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, technology and fossil fuels allowed governments to ignore ecological constraints temporarily. That era is ending.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is now formally recognised as the most water‑stressed region on the planet. According to global assessments of water risk, 16 of the 25 most water‑stressed countries are located here. Water stress in this context means that nations are using almost all of the renewable water resources they possess each year. Any slight decline in supply or modest increase in demand can tip them into acute crisis.

The underlying arithmetic is unforgiving. The region contains about 6 per cent of the world’s population, but only around 1.4 per cent of its renewable freshwater. The imbalance is structural; there is simply not enough renewable water for the people who depend on it, and the gap is widening.

The impact on the youngest generation is particularly stark. Nearly 90 per cent of children in MENA live in areas classified as experiencing high or extremely high water stress. Nine out of ten children are growing up in environments where the water system is already stretched to its limits, and where there is a real risk that taps could run dry in their lifetimes. This is not an abstract future threat; it is an everyday reality.

Vanishing Rivers and Dying Lakes

The region’s great rivers and lakes, which sustained ancient civilisations and nourished religious traditions, are now physical records of decline.

The Tigris and Euphrates – the rivers of ancient Mesopotamia, referenced in sacred texts and celebrated as the cradle of human civilisation – have lost an estimated 80 per cent of their flow since the mid‑1970s. The primary reason is not changing rainfall patterns but the construction of large dams upstream in Turkey, which severely restrict the volume of water reaching Syria and Iraq. What were once formidable rivers are, in places, reduced to diminished channels.

The Jordan River, central to the religious history of the region and particularly significant in Christian tradition, now runs at perhaps 10 per cent of its historical average. In some stretches, one can reportedly cross it on foot. Downstream, the Dead Sea, which depends on inflow from the Jordan and other sources, has been shrinking rapidly. Its level has fallen by over a metre per year in recent decades, leaving behind an eerie landscape of receding shoreline, abandoned hotels and treacherous sinkholes.

Lake Urmia in Iran provides one of the most dramatic illustrations of collapse. Once the second‑largest saltwater lake in the Middle East and the sixth‑largest of its kind on the planet, it held around 32 billion cubic metres of water in 1995. By late 2024 that volume had fallen to approximately half a billion cubic metres – a decline of about 95 per cent. Iranian officials have publicly acknowledged that the lake has “effectively dried up”.

By August 2025, warnings from Iranian leaders underlined the severity of the situation. The President cautioned that, without drastic change, dams could be empty by autumn. The exposed bed of Lake Urmia has become a source of salt‑laden dust storms capable of travelling up to 500 kilometres, depositing salt on farmland and in urban areas. Around 15 million people in north‑western Iran are now exposed to airborne particles that damage lungs, aggravate respiratory diseases and contaminate soil. Productive land is being gradually poisoned. Villages and towns face the prospect of long‑term depopulation.

Studies suggest that throughout at least 12,000 years of geological history, Lake Urmia had never previously dried out completely. What is now being witnessed is unprecedented on that timescale. The lake’s fate is not simply a story of changing climate; it is a testament to decades of unmanaged water extraction, dam‑building and agricultural expansion in an arid environment.

Human Mismanagement: Turning Water into Dust

While geography and climate set the stage, the current crisis is largely shaped by human decisions. Some of the most striking examples come from ambitious attempts to bend deserts to agricultural self‑sufficiency.

In Saudi Arabia during the 1980s and 1990s, the state embarked on an extraordinary project: to grow wheat at industrial scale in the desert and make the kingdom self‑reliant in basic food staples. Engineers and farmers tapped into a vast underground aquifer, believed to have formed tens of thousands of years ago during a wetter climatic era when the Arabian Peninsula was greener.

By the mid‑1990s, Saudi farmers were pumping an estimated 19 trillion litres of water per year. The results, at first glance, were spectacular. Satellite images showed great circles of irrigated green in the sand, produced by centre‑pivot irrigation systems. For a time, Saudi Arabia became the world’s sixth‑largest exporter of wheat.

Yet the apparent triumph concealed a structural flaw. The aquifer in question was essentially non‑renewable “fossil water”. Unlike rivers fed by annual rains or lakes replenished by snowmelt, this groundwater had accumulated over millennia under very different climatic conditions. Modern rainfall over the Arabian Peninsula was nowhere near sufficient to replace what was being extracted. Once removed, it would not return on any human timescale.

Within a few decades, more than 80 per cent of this ancient reserve had been depleted. By 2016, the Saudi government had effectively ended the domestic wheat‑growing programme. The fields vanished as fast as they had appeared. Today, the kingdom imports virtually all of the wheat it consumes. For a brief period, it had managed to transform finite water into grain. Within a generation, it was left with neither. The experiment stands as a stark example of what one might call slow‑motion resource suicide.

Iran offers a similar, and in some respects even more troubling, picture. Over 70 per cent of the country’s water use is devoted to agriculture, much of it squandered through highly inefficient techniques such as flood irrigation. In arid and semi‑arid regions, water‑intensive crops – including cotton and rice – have been cultivated on a large scale. Water has been applied broadly and wastefully, maximising immediate output but eroding long‑term viability.

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has built more than 600 dams across virtually every significant river system. Combined with aggressive groundwater pumping, this has pushed the country into what some experts describe as “water bankruptcy”: a situation in which commitments to water use far exceed sustainable supply. Lake Urmia has become the most visible symbol of this bankruptcy, but similar dynamics are evident in dried wetlands, collapsing aquifers and salinised soils across the country.

The common thread in these cases is the political choice to pursue short‑term agricultural gains and visions of self‑sufficiency without regard for hydrological limits. The technologies involved – pumps, dams, modern irrigation kit – gave governments the illusion of mastery over nature. In practice, they accelerated depletion.

Climate Change: A Relentless Amplifier

Overlaying these local and regional missteps is a global driver that is making everything worse: climate change. The Middle East and North Africa are warming at roughly twice the global average rate. While international negotiations debate abstract temperature targets, these countries are already experiencing the frontline consequences.

Heat records are being broken with increasing regularity. Summer temperatures that would once have been regarded as exceptional are becoming normal. Climate models project that most countries in the region will see rainfall decline by between 10 and 40 per cent by the end of this century, particularly during spring, which has historically been crucial for agriculture. Farmers who have depended on seasonal rains for millennia may find that the very pattern on which their planting calendars rest has shifted or vanished.

At the same time, higher temperatures increase evaporation. Projections suggest evaporation rates may rise from about 47 to 54 per cent in parts of the region. The result is a brutal equation: less water arriving from the atmosphere, and a higher proportion of it returning to the air before it can infiltrate soils, recharge aquifers or feed rivers.

By 2050, the amount of water available for irrigation across the Middle East could fall by 13 to 28 per cent. North Africa might see declines of 9 to 25 per cent. These estimates are based on relatively moderate emissions scenarios. They are not worst‑case extremes; they sit in the middle of the range of scientifically plausible futures.

If global temperatures rise by 2°C above pre‑industrial levels – a threshold often discussed as a “safer” limit – the Middle East is projected to lose more than 15 per cent of its already scarce water resources. At 4°C of warming, a level that remains possible towards the end of the century if emissions remain high, overall water availability could drop by around 45 per cent. Nearly half of what is already a meagre supply would be gone.

Beyond sheer quantities, rising heat poses a direct threat to human habitability. Research from the Max Planck Institute and others has highlighted the risk of wet‑bulb temperatures – a measure combining heat and humidity – reaching levels at which the human body can no longer cool itself through sweating. When the wet‑bulb temperature exceeds 35°C, even a healthy person resting in the shade with access to unlimited drinking water and air movement cannot maintain a safe core temperature. Prolonged exposure under such conditions is fatal.

Studies indicate that with 2°C of global warming, parts of the Middle East and North Africa could see regular periods in which outdoor work is dangerous or life‑threatening for months each year. At higher warming levels, some Gulf cities could experience conditions that surpass the survivability threshold for humans on a recurring basis.

This transforms the nature of the crisis. It is no longer only about irrigation, agriculture or industrial use. It becomes about whether outdoor labour is possible, whether infrastructure can function, and whether dense urban settlements can be kept cool and supplied with water. Air conditioning, in such a scenario, ceases to be a matter of comfort and becomes essential for survival – which raises its own questions about energy demand, power grid stability and inequality. When blackouts occur in such heat, those without backup systems or robust housing designs will be most exposed.

From Environmental Stress to Social Collapse

Environmental stress does not automatically translate into social breakdown. Communities can adapt, innovate and support one another. However, when societies are already fragile, when states are weak or corrupt, and when inequality is entrenched, water scarcity becomes an accelerant of crisis.

Somalia offers a stark illustration. Between 2022 and 2024, an estimated 71,000 people died from drought‑related causes there, according to joint assessments by international agencies and academic partners. The majority of the dead were children under five. These were not casualties of conventional warfare; they were victims of a lack of rain, dying livestock, crop failure and the resulting hunger and disease.

The 2020–2023 drought in Somalia, the worst in four decades, affected more than 8 million people – nearly half the national population. In 2023 alone, climate‑related shocks displaced around 2.9 million individuals. Wells and boreholes dried up. Entire herds, the main assets of pastoral communities, perished. Villages that had eked out an existence on marginal land for generations found themselves with nothing to drink and nothing to eat.

Families walked for days across parched landscapes in search of food distribution centres or basic medical help. Some never arrived. Camps for internally displaced people expanded rapidly, filled with people whose homes had not been destroyed by bombs but rendered unliveable by empty wells and failed harvests. What pushed them to move was not artillery or air raids, but simple thirst and hunger.

Syria demonstrates how environmental disaster can interact with pre‑existing political tensions to produce catastrophe on a far greater scale. From 2006 to 2010, the country experienced its worst drought on the instrumental record, and likely the worst in the broader Fertile Crescent region in at least nine centuries. Rainfall collapsed. Nearly two‑thirds of farms failed. Farmers who had been compensating for earlier shortfalls by pumping groundwater found that aquifers had been drawn down too far; the water was gone.

The north‑eastern region of Syria, traditionally its main grain‑producing area and responsible for around 65 per cent of its wheat, was devastated. Crop yields plummeted. Livestock died in large numbers. Rural incomes evaporated.

In response, between one and 1.5 million people left their land and moved to urban centres such as Aleppo, Damascus and Homs. This was not the familiar pattern of young men moving in search of seasonal work. Entire families, including grandparents and children, abandoned their villages. They arrived in the outskirts of cities already housing growing populations and significant numbers of Iraqi refugees from earlier conflicts. By 2010, internally displaced Syrians and foreign refugees accounted for about a fifth of the urban population. In less than a decade, some cities had expanded by more than 50 per cent.

Food prices rose. Unemployment increased. Former farmers, with limited formal education and few contacts in urban labour markets, struggled to find any work. Meanwhile, the government removed fuel subsidies and provided minimal support to those affected by the drought. A sense of abandonment, frustration and injustice spread.

When protests began in 2011 as part of the broader wave of uprisings commonly termed the Arab Spring, these grievances helped to fuel the movement. Analyses by scientific academies have concluded that human‑induced climate change made the severe Syrian drought two to three times more likely than it would otherwise have been. The people displaced by the drought were disproportionately represented among those opposing the regime. What began as peaceful demonstrations evolved into a brutal civil war, with hundreds of thousands of deaths and millions of displaced people, in part along fault lines deepened by environmental stress.

Water, Protest and Fragile States

Similar patterns of unrest linked to water scarcity are emerging elsewhere in the Islamic world, even where full‑scale war has not yet broken out.

In Algeria, for example, the desert town of Tiaret saw violent protests in 2024 following months of intermittent or absent water supply. Residents queued for hours to fill containers from limited sources. Promised remedies failed to materialise. When patience ran out, anger spilled into the streets. Police were deployed, clashes broke out, and property was damaged. The immediate trigger was not ideology or ethnic division, but the state’s inability to provide the most basic necessity of life.

In Iran, protests over water have become a recurring feature of political life. In 2021, demonstrations erupted in Khuzestan province, a region historically known for its rivers and wetlands. Rivers had been diverted, wetlands had dried out and taps in many communities ran dry or delivered only contaminated water. People took to the streets chanting, “I am thirsty”, a slogan focusing attention solely on the denial of a fundamental right. The government responded with security forces; shots were fired, and protesters were killed. The demand at the heart of the protests was simple: access to clean water.

Yemen faces perhaps the most acute urban water crisis of all. Already mired in a devastating civil war, the country’s capital, Sana’a, is projected by some analyses to be on course to become the first major city in the world to literally run out of economically accessible water. The aquifer underlying the city has been drawn down for years to supply a growing population and water‑intensive crops in the surrounding region, including qat, a mild narcotic widely chewed across the country. Some estimates suggest that the accessible groundwater near Sana’a could be exhausted within years rather than decades.

In many rural parts of Yemen, communities already engage in armed confrontations over wells and springs. Water is no longer merely scarce; it is weaponised. Armed groups and local power brokers fight to control wellheads and pumping stations. In cities under siege, water supply is sometimes cut off deliberately to coerce populations. The country’s water crisis is inseparable from its broader conflict; each exacerbates the other.

Across Borders: Rivers, Dams and Emerging “Water Wars”

Water does not respect political borders. Rivers often flow through several countries, and aquifers may underlie multiple states. As supplies become more constrained, regional tensions are sharpening.

Egypt illustrates the vulnerability of a downstream nation. More than 90 per cent of its water comes from the Nile, and over 100 million Egyptians live along its banks. The river is not simply a geographical feature; it is the foundation of Egyptian civilisation. Without it, agriculture on the current scale would be impossible and many cities would be unsustainable.

Ethiopia, however, has constructed the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile, the river’s main tributary and the principal source of water and silt for Egypt. Once fully operational, the dam will give Ethiopia significant control over the timing and volume of water flowing downstream. Egyptian officials, including former presidents, have openly discussed the possibility of military action if their vital interests are threatened. Diplomatic negotiations continue, but a durable agreement has yet to be fully secured. The spectre of conflict over Nile waters remains present.

Further north, Turkey’s extensive dam‑building on the Euphrates and Tigris systems has already reduced the flow of water into Syria and Iraq by around 80 per cent since the 1970s. In southern Iraq, once‑fertile marshlands that supported distinctive ways of life for thousands of years have largely disappeared or shrunk dramatically. Farmers in these regions observe their fields turning to dust and salt while Turkish reservoirs and hydroelectric facilities thrive further upstream. Disputes over water allocations simmer beneath already complex political relationships.

In Central Asia, where several countries are Muslim‑majority or have significant Muslim populations, glaciers in the high mountains are retreating due to warming. Rivers fed by these glaciers supply water to downstream nations. Upstream states such as Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan possess the headwaters and have built, or plan to build, dams for hydroelectric power and irrigation. Downstream Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, reliant on these flows for agriculture and drinking water, view such projects with concern. Soviet‑era water‑sharing agreements are under strain, and regional rivalries are intensifying.

The phrase “water wars” once belonged more to the realm of speculative fiction than immediate geopolitics. The conflicts now emerging are often not declared as wars over water: they are framed in terms of national security, development, territorial control or minority rights. Yet water lies at the heart of many disputes, and as supplies become more erratic, the likelihood of open conflict linked to rivers and aquifers increases.

Turning to Heaven: Faith, Prayer and the Limits of Spiritual Response

Against this backdrop of physical scarcity and political tension, millions of people across the Islamic world are turning to a different source of comfort and hope: communal prayer.

In late 2024 and into 2025, as forecasts warned of yet another dry winter, numerous countries in the region organised mass prayers for rain, known as Salat al‑Istisqa. This special prayer, deeply rooted in Islamic tradition, is performed to seek divine mercy in times of drought. It is one of the most solemn communal rituals in the faith, dating back to the Prophet Muhammad.

In Saudi Arabia, King Salman publicly called for nationwide prayers for rain, urging “every capable person” to attend mosques and supplicate for relief. Across the kingdom, from the sprawling cities of Riyadh and Jeddah to small desert settlements, mosques filled during the early hours of the day. Voices rose together in a collective plea for water.

Kuwait reportedly held 125 simultaneous prayer gatherings in mosques on a single day. The United Arab Emirates organised similar observances. Even in Iran, where the government bears considerable responsibility for the mismanagement of water resources, officials and religious leaders encouraged the population to ask Allah for rain.

In some places, worshippers turned their clothing inside out, following long‑standing tradition as a symbol of humility and a desire to see their harsh circumstances reversed. The image of entire communities gathered in open spaces, eyes turned skywards, is both moving and sobering.

These ceremonies represent a profound cultural and spiritual response to suffering. They reinforce social bonds, provide psychological comfort and express a shared recognition of human dependence on forces beyond human control. At the same time, critics within these societies point out that while prayer can unify and console, it cannot by itself refill aquifers, reverse the over‑building of dams or change agricultural policies.

When the congregations disperse and believers scan the horizon for clouds, an uncomfortable question hangs in the air: what if the hoped‑for rain does not come, or comes only briefly? Without accompanying reforms in water management, energy policy and climate mitigation, faith alone cannot stabilise the hydrological cycle.

Towards a Century of Displacement?

If current trends continue, the region is heading towards levels of water scarcity that are incompatible with stable, prosperous societies on anything like their present scale.

By 2030, projections from international development institutions suggest that average water availability in the Middle East and North Africa could fall below 500 cubic metres per person per year. This figure is known as the “absolute scarcity” threshold. Below it, water is simply too limited to support normal economic and social functioning. For context, the current global average stands around 7,000 cubic metres per person per year. Residents of Europe and North America typically have access to well over 1,500 cubic metres. The difference is vast.

By 2050, two‑thirds of countries in the region may find themselves with less than 200 cubic metres of water per person annually. At that level, large‑scale agriculture becomes nearly impossible. Industrial development is constrained. Even guaranteeing drinking water and minimal sanitation becomes a serious challenge.

The movement of people has already begun. More than one million Somalis were displaced in 2022 alone, driven largely by climate‑related shocks and drought. Hundreds of thousands more followed in 2023. Syrian refugees, whose displacement was shaped in part by drought‑linked rural collapse before the war, now number in the millions, spread across Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and beyond.

Climate‑related migration from North Africa, the Sahel and South Asia towards Europe is already visible in the form of perilous crossings of the Mediterranean and dangerous journeys across deserts. Thousands have died attempting these routes. Behind many of those journeys lies not just conflict or poverty, but long‑term environmental degradation and shrinking water supplies.

If significant portions of the Islamic world become too hot or too dry to sustain their populations, the scale of potential displacement is immense. Tens of millions of people could be forced to move within their own countries, to neighbouring states or further afield. This would not unfold in some remote future; it would occur within the lifetimes of children alive today.

These future migrants would, in many cases, be fleeing neither bombs nor ideology, but basic climatic and hydrological realities: wells that have run dry, rivers reduced to polluted trickles, and temperatures that make outdoor labour lethal. Behind the headlines about conflict, extremism or political upheaval, the deeper story may increasingly be one of water – its absence, its mismanagement and its redistribution under a warming sky.

Conclusion: An Unfolding Crisis, Not an Inevitable Fate

The water crisis unfolding across much of the Islamic world is not a distant threat or a purely future scenario. It is already claiming lives, unravelling livelihoods, destabilising governments and redrawing migration routes. Rivers with biblical histories have been diminished. Vast lakes that anchored regional identities have receded to the point of disappearance. Children are growing up in towns where water scarcity is normal, not exceptional.

Yet this trajectory, while grave, is not entirely beyond human influence. Climate change will continue to tighten constraints, but the pace and severity of its impact still depend on global emissions choices. Within the region, water use can be made more efficient; cropping patterns can be altered; fossil aquifers can be protected from further depletion; cities can be redesigned with conservation and resilience in mind.

What the present moment reveals most clearly is that the combination of ancient aridity, modern over‑extraction and accelerating climate change is unsustainable. For centuries, Islamic civilisation flourished in these harsh environments through sophisticated water management, social cooperation and an intimate understanding of local ecologies. In the twentieth century, cheap energy and large‑scale engineering fostered an illusion that technology alone could overcome geography. That illusion is now dissolving.

The question facing governments and societies across the region is whether they can rediscover forms of stewardship appropriate to today’s conditions: policies that respect planetary limits, acknowledge shared rivers and aquifers, and plan for a hotter, drier world. Failing that, water will continue to act as an unforgiving judge of human decisions, reshaping the map of populations and power in ways that no ideology or army can fully control.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which nations are currently facing the highest levels of water stress?

The crisis is most acute in the Middle East and North Africa, a region that contains sixteen of the twenty-five most water-stressed countries on Earth. Egypt is particularly vulnerable, receiving an average of only 18 millimetres of rainfall annually and relying almost exclusively on the Nile for its survival. Other nations such as Libya, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates also face extreme scarcity, with annual rainfall totals often failing to reach 100 millimetres. These countries are currently consuming nearly all of their renewable water resources, meaning any further decline in supply or increase in demand could lead to a total systemic failure.

To what extent is human mismanagement responsible compared to climate change?

While climate change acts as a relentless amplifier, much of the current crisis is the result of decades of poor policy and engineering choices. In countries like Iran, “water bankruptcy” has been driven by the construction of over 600 dams and the use of inefficient flood irrigation for water-intensive crops like rice and cotton in arid zones. Similarly, upstream dam projects, such as those built by Turkey on the Tigris and Euphrates, have slashed water flow to downstream neighbours by up to 80 per cent. These human interventions, combined with the over-extraction of groundwater, have depleted ecosystems far faster than natural climate variability alone would have dictated.

What is “fossil water” and why is its depletion so significant?

Fossil water refers to ancient underground aquifers that were filled tens of thousands of years ago during previous ice ages when the climate was significantly wetter. Because these reserves are not replenished by modern rainfall, they are a finite, non-renewable resource. Saudi Arabia’s attempt to become a global wheat exporter in the 1980s and 90s relied on pumping trillions of litres of this fossil water, which resulted in the depletion of over 80 per cent of the aquifer in just a few decades. Once these ancient reserves are exhausted, the agricultural systems and communities that depend on them have no alternative source of water, leading to total land abandonment.

How does water scarcity contribute to regional conflict and civil unrest?

Water scarcity often acts as a “threat multiplier” that turns existing social tensions into open conflict. In Syria, the worst drought in 900 years caused a rural collapse that forced 1.5 million people into urban slums, creating the economic desperation that helped ignite the 2011 civil war. More recently, “water riots” have broken out in places like Tiaret, Algeria, and Khuzestan, Iran, where citizens have taken to the streets to protest dry taps and government mismanagement. On an international level, tensions are rising between Egypt and Ethiopia over the Nile, and between Iraq and Turkey over the Euphrates, raising the very real prospect of future “water wars” over shared river systems.

What are the projected long-term impacts on human habitability in the region?

The long-term outlook suggests that large swathes of the region may become effectively uninhabitable by the middle of the century. If global temperatures rise by 2°C, parts of the Middle East could experience “wet-bulb temperatures” exceeding 35°C, a threshold at which the human body can no longer cool itself through sweating, making outdoor survival impossible. Furthermore, the World Bank projects that average water availability in the region will soon fall below the “absolute scarcity” threshold of 500 cubic metres per person. This level of depletion would make it impossible to sustain modern industry or agriculture, potentially triggering the largest mass migration event in human history as tens of millions of people seek cooler, wetter climates.