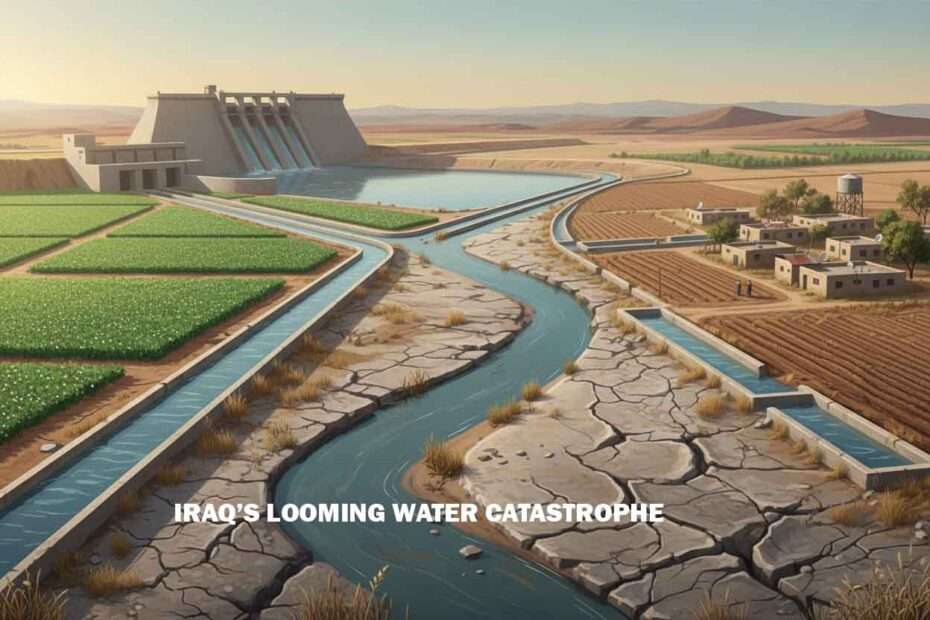

Iraq’s Looming Water Catastrophe

The Tigris at a Turning Point: Turkey’s Dam and the Tigris at a Turning Point:

The Tigris River, stretching roughly 1,900 kilometres from its source in the Taurus Mountains of Turkey to the lowlands of southern Iraq, has shaped human civilisation for millennia. Flowing briefly along the Turkish–Syrian border and then across Iraq for more than 1,400 kilometres, it is more than a geographical feature. For Iraq in particular, it is a lifeline: a critical artery for drinking water, agriculture, ecosystems and social stability.

Yet in recent decades, this ancient river has become the focus of a deeply modern conflict over resources, development and survival. Upstream, Turkey has pursued an ambitious dam-building programme designed to transform its own arid regions, drive industrial growth and reduce dependence on imported energy. At the heart of this strategy lies an extensive diversion of water to support intensive cotton cultivation and hydroelectric power. Downstream, Iraq faces mounting water shortages, ecological collapse and social strain.

This article examines how Turkey’s large-scale dam projects on the Tigris and Euphrates—especially the Ilısu Dam—have contributed to a profound water crisis in Iraq. It also explores the wider regional and global implications of this struggle, from the destruction of ancient heritage sites to the reshaping of international river politics.

Cradle of Civilisation: Why the Tigris Matters to the World

The banks of the Tigris and Euphrates form the heart of Mesopotamia, often referred to as the “cradle of civilisation”. Archaeological and scientific evidence suggests that around 8,000 years ago, some of the first settled human communities emerged here. Early farmers began cultivating crops and raising livestock, while small settlements evolved into some of the earliest cities known to history, such as Eridu, Ur and Uruk.

From this region emerged innovations that underpin modern societies:

- Early systems of writing

- The invention of the wheel

- Codified legal frameworks

- Organised agriculture and irrigation

These developments transformed scattered communities into organised states and laid the foundations of complex social, economic and political systems.

Despite this profound legacy, the modern Tigris is often overshadowed by narratives of conflict. Decades of war and political upheaval have obscured the river’s ongoing centrality to life in Iraq. Yet this centrality remains starkly evident in basic statistics. Almost all of Iraq’s drinking water, household water and irrigation depends on the Tigris and its twin river, the Euphrates. Estimates suggest that around 98–99% of Iraq’s surface water comes from these two rivers alone. There is effectively no alternative large-scale source: no significant glaciers, snowpacks or other major rivers to compensate for any loss of flow.

Against this backdrop, changes in upstream water management are not technical adjustments; they are existential threats.

Turkey’s Pressures: Population, Energy and Regional Inequality

To understand why Turkey has invested so heavily in dams on the Tigris and Euphrates, it is necessary to consider the domestic pressures shaping its policy.

Over the past four decades, Turkey’s population has nearly doubled, rising from roughly 45 million to more than 85 million. This rapid growth has been accompanied by intense urbanisation. Major metropolitan centres such as Istanbul and Ankara consume more electricity, water and food every year. Meanwhile, energy-intensive heavy industries—including steel, cement and textiles—require a stable and affordable power supply to remain competitive.

Crucially, Turkey is not self-sufficient in fossil fuels. It is heavily reliant on imported oil and natural gas, exposing the economy to global price volatility. Between 2021 and 2022, the country’s energy import bill alone reportedly exceeded 90 billion US dollars, placing extreme pressure on the national currency and broader macroeconomic stability.

These national challenges are magnified in southeastern Anatolia, an historically poorer and drier region with high unemployment and limited economic opportunities. For the Turkish government, the logic is straightforward:

- Without water, there can be no viable agriculture.

- Without agriculture, jobs disappear.

- Without jobs, social instability grows.

Large dams therefore serve several purposes simultaneously:

- Generating electricity to reduce dependency on imported energy

- Creating extensive irrigation networks to support agriculture

- Providing a basis for rural employment and discouraging out‑migration

This multi-layered rationale is embodied in one of the most ambitious regional development plans in Turkey’s history: the Southeastern Anatolia Project, often known by its Turkish acronym, GAP.

The Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP): A Mega-Scheme with Mega-Consequences

The vision of harnessing the waters of southeastern Anatolia dates back decades, but it was during the 1970s and 1980s—amid accelerating industrialisation and rising energy import pressures—that the project crystallised into a single, integrated mega-scheme.

GAP covers more than 75,000 square kilometres, roughly 10% of Turkey’s total land area. It directly affects between eight and nine million people. For comparison, the project area is almost as large as Austria. With an investment estimated at around 32 billion US dollars, it is one of the largest regional development initiatives ever undertaken in Turkey.

The project is managed by the State Hydraulic Works, Turkey’s most powerful authority on water resources, underscoring its strategic importance. Its goals are multi-dimensional:

- Alleviate chronic electricity shortages

- Expand irrigation and agricultural output

- Reduce unemployment

- Combat long‑standing poverty in southeastern Anatolia

At the heart of GAP are 14 major dams on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, linked to thousands of kilometres of irrigation canals. These structures regulate river flows, store large volumes of water and divert them onto farmland that was previously dependent on unpredictable rainfall.

Among these, the Atatürk Dam on the Euphrates became the project’s flagship and proof-of-concept.

Atatürk Dam: Transforming an Arid Region into a Cotton Powerhouse

Completed in 1992, the Atatürk Dam represented a turning point for Turkey’s hydroelectric and irrigation ambitions. Standing about 169 metres high and spanning roughly 1,820 metres, its reservoir can hold around 49.2 cubic kilometres of water. The dam’s installed capacity of approximately 2,400 megawatts allows it to generate nearly 8,900 gigawatt hours of electricity each year—sufficient to power a small European country such as Latvia with capacity to spare.

For many years, Atatürk contributed a substantial proportion of Turkey’s total hydroelectric output. Yet its influence extended far beyond energy. The combination of a massive reservoir and a sophisticated irrigation network radically changed the agricultural landscape of southeastern Anatolia.

Previously, farmers in this region were limited by an arid climate and highly variable rainfall. They relied on drought-resistant crops with modest economic returns. The arrival of reliable, year‑round irrigation enabled a shift to water-intensive but more lucrative crops, most notably cotton.

Cotton offers much higher market value than many traditional cereals. However, it comes with a heavy water footprint. Agricultural studies estimate that producing one kilogram of raw cotton may require between 7,000 and 10,000 litres of water—several times more than cereal crops. Each new hectare of cotton cultivation therefore represents a significant volume of water that is retained and diverted from the natural river system.

Before GAP, cotton production in southeastern Anatolia was constrained by unreliable irrigation and did not exceed roughly 150,000 tonnes per year. Less than a decade after the expansion of large-scale irrigation, production had nearly tripled, reaching around 400,000 tonnes by 2001. Today, the region accounts for close to 60% of Turkey’s total cotton output.

In economic terms, the transformation was a success story: an area once marginal and water‑stressed emerged as a major export-oriented cotton producer with higher local incomes. However, this success depended on retaining vast quantities of water that would otherwise have flowed downstream, primarily to Syria and Iraq.

At this stage, international responses to Atatürk were comparatively muted. Concerns were voiced about changes in river flow and population displacement, yet they did not escalate into a full-blown regional crisis. For Turkey, domestic benefits—in electricity generation, agricultural production and export revenue—were visible and immediate. The long-term downstream consequences remained distant, both politically and geographically.

The Ilısu Dam: Blocking the Lifeline of Iraq

After Atatürk, GAP entered an aggressive expansion phase, with a succession of new dams across both the Euphrates and Tigris. Hydropower capacity increased steadily and irrigated agriculture flourished.

The Ilısu Dam, however, marked a qualitative shift. Unlike Atatürk, which sits on the Euphrates, Ilısu was built directly on the Tigris—the river upon which Iraq depends for the overwhelming majority of its drinking water, agriculture and ecological integrity.

With a total cost of around 1.7 billion US dollars, Ilısu ranks alongside some of the world’s major mega-dams. Yet from its inception it was mired in controversy, not only for its environmental and social impact, but also for the cultural heritage it threatened and the cross-border implications for Iraq.

Financing Battles and International Backlash

From the outset, Ilısu became the most politically sensitive component of GAP. Environmental groups, human rights organisations and heritage conservation bodies argued that this was not merely an internal Turkish development project. They warned of severe ecological degradation downstream, human displacement and the destruction of invaluable archaeological sites.

Turkey initially pursued international financing, with particular interest from European institutions. However, comprehensive impact assessments raised serious concerns. The project was expected to meet more than 150 international standards relating to:

- Environmental protection

- Resettlement and compensation

- Heritage conservation

- Transboundary water impacts

Ilısu failed to comply within the stipulated timeframes. In response, the United Kingdom withdrew a guarantee package worth approximately 236 million US dollars. Germany, Switzerland and Austria followed suit, pulling a further 610 million US dollars in guarantees and loans. On paper, the project appeared close to being halted.

Instead, Turkey opted to proceed with predominantly domestic financing, accepting significant delays and mounting international criticism. Construction, which began around 2006, faced further obstacles, including armed attacks in 2014. Yet the site remained operational. By 2018, the structure was complete.

The Ilısu Dam stands roughly 135 metres high and stretches about 1,829 metres in length. Its reservoir can hold approximately 10.4 cubic kilometres of water. This storage capacity allows extensive new irrigated areas to be created, particularly for cotton cultivation, while contributing additional hydroelectric output. Ilısu has an installed capacity of around 1,200 megawatts, generating an estimated 3,800 gigawatt hours of electricity annually.

Turkey presented the dam as a source of employment—claiming around 10,000 jobs during construction and operation—and as a catalyst for tourism centred on the new reservoir.

For Iraq, however, Ilısu was not a development opportunity. It was a looming threat.

A Legal Vacuum: “Transboundary” Versus “International” Rivers

The most deeply troubling aspect of Ilısu lies in the legal and institutional context of the Tigris–Euphrates basin. Unlike rivers such as the Danube in Europe or the Nile in Africa, there is no comprehensive, binding water-sharing treaty governing these flows. Many major international rivers are subject to agreements setting minimum discharge levels, mandatory release rules and multilateral monitoring mechanisms. The Tigris and Euphrates have no such overarching framework.

Turkey’s position is distinctive. Ankara does not recognise the Tigris and Euphrates as “international” rivers in the classic legal sense. Instead, it refers to them as “transboundary” rivers, arguing that within its territory the waters are part of its national sovereign resources. Under this interpretation, Turkey does not accept a binding obligation to maintain a fixed volume of water flowing into Syria or Iraq.

Existing arrangements are largely political and ad hoc, rather than treaty-based. They can be revised, ignored or reinterpreted according to shifting domestic priorities and regional power dynamics.

For Iraq—situated entirely downstream—this is a position of acute vulnerability. The vast majority of its surface water arrives via the Tigris and Euphrates from Turkey (and to a lesser extent from Iran). If 60–70% of this incoming flow were to diminish, the consequences would be catastrophic. For Iraq, this is not an abstract scenario. It is what is progressively occurring.

Iraq’s Water Crisis: From Taps to Fields to Marshes

When Ilısu’s reservoir began to fill, there was no formal declaration that a crisis had begun. No headline announcement signalled a new era of scarcity. Yet hydrological monitoring stations in Iraq began to record harsh realities.

During dry seasons, some locations registered only 30–40% of the Tigris’s historical average flow. To imagine the implications, it is helpful to translate these percentages into everyday terms. If a household suddenly had only one-third of its usual water supply, difficult choices would be unavoidable: prioritising drinking over cooking, hygiene over cleaning, or vice versa. On a national scale, such cutbacks carve deeply into public health, agriculture and industry.

Public Health and Drinking Water

In Iraq’s southern provinces—such as Basra, Dhi Qar and Maysan—the decline in river flow has coincided with deteriorating water quality. Tap water in many areas is no longer potable and, in some cases, not even safe for contact with skin. Salinity levels have risen dramatically, giving the water a distinctive salty taste and causing skin irritation. High salinity also corrodes pipes and water infrastructure, driving up maintenance costs and further undermining service reliability.

Between 2018 and 2022, more than 100,000 residents in Basra alone were reportedly hospitalised with illnesses linked to polluted or saline water, including acute diarrhoea, salt poisoning and skin conditions. Here, water scarcity is not an abstract environmental concern; it is visible in every hospital ward, every household struggling to secure safe drinking water and every child suffering from dehydration or water-borne diseases.

Agriculture and Food Security

Agriculture remains a critical employer in Iraq, directly or indirectly sustaining roughly one-third of the workforce. It is acutely dependent on predictable irrigation from the Tigris and Euphrates. As the Tigris’s flow declines, tens of thousands of hectares of farmland no longer receive adequate water.

In parts of southern Iraq, farmers who previously grew wheat on areas as large as 10 square kilometres now find themselves unable to cultivate anything at all. As one farmer in Dhi Qar reportedly observed, the problem was not the harvest being lost; the water disappeared before seeds could even be sown.

Confronted with these realities, the Iraqi government has been compelled to impose unprecedented restrictions on water-intensive crops. Cultivation of rice and wheat has been cut back, with water prioritised for domestic use rather than agriculture. While necessary in the short term, these measures increase Iraq’s reliance on imported food at a time when its economy faces significant strain.

When a country loses the capacity to feed itself, particularly as its water reserves dwindle, broader questions of political and social stability inevitably arise.

Sediment, Salinity and Environmental Degradation

Reduced river flow is not the only consequence of upstream dams. Reservoirs trap large quantities of sediment—estimates suggest between 70 and 90% in some cases. For thousands of years, this sediment nourished Iraq’s alluvial plains, replenishing soil fertility and providing a natural buffer against salinisation.

Without regular sediment deposits, agricultural soils degrade rapidly. Weaker river flows permit salt water from the Persian Gulf to push further inland up the Shatt al‑Arab and connected channels. In the absence of sufficient fresh water to flush these salts back towards the sea, salinity accumulates in the soil. Fields that were once fertile become white, hardened and cracked—visual markers of long-term land degradation that is difficult and expensive to reverse.

The Collapse of the Mesopotamian Marshes

Perhaps the most striking ecological casualty of the changing Tigris–Euphrates system is the Mesopotamian marshes, once the largest wetland ecosystem in the Middle East and a globally significant ecological and cultural landscape. These marshes are entirely dependent on robust freshwater inflows from the Tigris and Euphrates.

As flows weaken and salinity increases, aquatic vegetation dies, fish stocks collapse and water buffalo—central to local livelihoods—struggle to survive. Field reports depict buffalo carcasses washed up along shrinking shorelines and formerly lush green vistas turning first yellow, then brown, and ultimately white with crystallised salt.

For the Maʻdān, or Marsh Arabs, who have lived in close connection with this environment for generations, this is not simply an environmental loss. It is the erosion of an entire way of life. Without water, grazing land or viable fisheries, many families have few options but to abandon their homes and migrate to already overstretched cities such as Basra and Baghdad.

This rural exodus contributes to rising unemployment, urban poverty and social tension. Some regional analysts argue that the slow-moving water crisis has quietly intensified Iraq’s instability since around 2011, intertwining with political grievances and economic hardship.

A Unique Ecosystem Under Threat: Endemic Species of the Tigris–Euphrates

Beyond human communities, the Tigris and Euphrates basin hosts an unusually high level of endemic species—organisms found nowhere else on Earth. Several freshwater fish species, including the Tigris giant carp and the Tigris striped carp, rely on natural river flows and seasonal migration routes for spawning.

Large dams fragment these habitats. Sudden changes in water levels and the loss of migration pathways disrupt breeding cycles. Many of these species cannot adapt to reservoir environments or relocate to other river systems. When their populations decline, they face extinction with no “backup” populations elsewhere in the world.

The consequences of Ilısu and similar structures are therefore not limited to the immediate region. They erode global biodiversity and further destabilise already fragile ecosystems.

Iraq’s Internal Challenges: An Antiquated and Leaky Water System

While upstream dams play a central role in Iraq’s water crisis, they are not the sole cause. Long-standing internal weaknesses have amplified the impact of reduced river flows.

Iraq’s irrigation infrastructure is severely outdated and inefficient. International assessments suggest that only about 20% of irrigation canals are lined with concrete. The rest are earthen channels through which water seeps and evaporates before reaching fields. The result is analogous to pouring water into a bucket riddled with holes: the more volume added, the more is wasted.

Most pumping stations and hydraulic control structures date back to the 1970s, a period when the Tigris and Euphrates carried significantly more water and Iraq’s population was roughly half its current size. Decades of conflict, sanctions and underinvestment have left this infrastructure in a state of disrepair. Some studies indicate that water loss rates in certain areas reach 50–60%. In effect, Iraq loses half of its remaining water through inefficiency before it can even be applied productively.

Rehabilitating canals, modernising irrigation technology, improving governance and managing demand are all critical steps. Yet these internal reforms, while essential, do not negate the scale of the challenge posed by upstream retention and diversion.

Cultural Heritage Underwater: The Submergence of Hasankeyf

The social and ecological costs of Ilısu are mirrored by cultural losses. One of the most poignant examples is Hasankeyf, an ancient settlement on the Tigris with a history stretching back around 10,000 years. Over the centuries, it has been shaped by Bronze Age communities, Roman and Byzantine authorities, Islamic dynasties and the Ottoman Empire.

Hasankeyf contained thousands of caves, temples, tombs and fortifications. Remarkably, even into the 21st century, people were still living in dwellings carved into rock faces that bore witness to multiple civilisations. Turkey itself had acknowledged the settlement’s historical importance, placing it under domestic protection.

When Ilısu was planned downstream, however, the fate of Hasankeyf was effectively sealed. Scholars and international organisations called for its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but the Turkish government never formally submitted the application. The World Monuments Fund later listed Hasankeyf among the 100 most endangered heritage sites worldwide, yet this recognition did not alter the project trajectory.

As Ilısu’s reservoir filled, most of Hasankeyf was gradually submerged. A handful of significant structures, such as the tomb of Zeynel Bey, parts of the historic city gate and several medieval Islamic monuments, were relocated in complex engineering operations. A new town was built to house displaced residents. Nonetheless, the majority of the site—including extensive cave complexes and archaeological layers never fully excavated—was lost underwater.

This outcome highlights a stark paradox. While the newly formed reservoir is promoted as a tourist attraction, the flooding of a unique 10,000‑year-old city represents an irreplaceable loss for global heritage.

Ilısu’s footprint extends beyond Hasankeyf. Approximately 199 settlements are thought to have been directly or indirectly affected, displacing tens of thousands of people. Numerous archaeological sites that had never been systematically documented disappeared beneath the rising water. The dam also disrupts fish migration, driving down populations of already stressed species such as the Euphrates softshell turtle and contributing to a cascade of ecological changes along the Tigris corridor.

A Global Pattern: Upstream Power, Downstream Vulnerability

The story of the Tigris and Ilısu is not an isolated case. Around the world, major rivers are being reshaped by large infrastructure projects undertaken by upstream states, often in the absence of robust, enforceable international agreements.

The Mekong

The Mekong River, flowing approximately 4,350 kilometres through six countries in South-East Asia, sustains tens of millions of people. About 95% of its upper course lies within China, where it is known as the Lancang. Over the past two decades, China has built 11 large dams on its upper reaches.

These structures have significantly altered hydrological and sediment patterns downstream. Sediment delivery has reportedly fallen by around 50%. Dry-season water levels have dropped to record lows across several years in stretches of Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Viet Nam.

In Cambodia and Viet Nam, where local livelihoods depend heavily on sediment-rich floodplains and fisheries, the impacts have been severe. In Viet Nam’s Mekong Delta, saltwater intrusion has pushed 50 to 70 kilometres further inland. Farmland is subsiding and agricultural land is gradually losing its fertility and productivity.

China, like Turkey, has often treated the river as a strategic asset under its own jurisdiction, without recognising it as an international river subject to binding allocation rules. Decision-making is therefore heavily skewed towards the upstream state, while downstream countries are left to adapt to changed conditions.

The Nile

The Nile basin offers another highly charged example. Around 85% of the Nile’s water reaching Egypt originates from the Ethiopian highlands via the Blue Nile. Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), with a reservoir capacity of roughly 74 cubic kilometres and an installed capacity of about 6,450 megawatts, is set to become Africa’s largest hydroelectric facility.

For Ethiopia, GERD is a symbol of national development and a route out of chronic energy poverty. For Egypt—where approximately 97% of freshwater relies on the Nile—any reduction or unpredictable variation in flow poses serious risks to food security and long-term planning. Despite more than a decade of negotiations involving Sudan as well, no final binding agreement has been reached on filling and operating the dam.

The language of the debate is familiar: upstream countries invoke their right to development and energy security, while downstream nations emphasise their right to survival and historical usage.

The Indus

Even when functioning treaties exist, disputes persist. The Indus River system, crucial to Pakistan’s agriculture—around 90% of which depends on its waters—originates largely in India. The 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, often hailed as a model of cooperative river management, has come under strain as India expands its own hydropower infrastructure on upstream tributaries.

Pakistan fears that, despite formal allocations, upstream control over storage and flow timing could compromise its own water security. Given the history of conflict and the nuclear capabilities of both countries, water in this context is not simply a resource; it is a strategic factor with potential implications for regional stability.

Across these cases, a pattern emerges: where international water law and cooperative mechanisms are weak or absent, physical geography often dictates power relations. Upstream states wield considerable leverage; downstream states bear disproportionate risks.

An Unfinished Story: What Ilısu Signals for the Future

Ilısu is not the final dam envisioned within GAP, nor is it the last major structure planned on the Tigris–Euphrates system. A combination of existing, under‑construction and proposed projects suggests that further regulation and impoundment of the rivers is likely.

For Iraq, Ilısu thus represents not only a current challenge but also a dangerous precedent. As climate change continues to make the Middle East hotter and drier, every cubic metre of water retained upstream becomes more valuable economically and politically. Yet each additional unit of water held back also intensifies scarcity downstream.

The Ilısu case illustrates a broader, unsettling reality: when the evolution of international water law lags behind technological capability and political ambition, the distribution of power is determined more by geography than by principles of equity or sustainability. The upstream nation can pursue development with relatively few legal constraints; the downstream nation is compelled to adapt, absorb the impacts or attempt to negotiate from a structurally weaker position.

Between Development and Survival: The Unresolved Question

The Tigris and Euphrates are more than lines on a map. They are deeply embedded in the history of human civilisation and in the day‑to‑day survival of millions of people. Today, they sit at the intersection of several pressing global issues:

- Energy transitions and the pursuit of hydroelectric power

- Food security and agricultural expansion

- Climate change and increasing aridity

- Biodiversity loss and cultural heritage destruction

- Weak or outdated international governance mechanisms

The core dilemma is as simple as it is profound: where should the boundary lie between one country’s right to develop and another’s right to survive?

In the case of the Tigris, Turkey has argued for the primacy of domestic needs—energy security, regional development, agricultural prosperity and poverty reduction. Iraq, meanwhile, faces poisoned tap water, failing crops, collapsing wetlands, displaced communities and a degraded environment.

Resolving this tension requires more than rhetorical appeals. It calls for robust, enforceable frameworks that treat transboundary rivers not merely as resources within national borders but as shared assets whose sustainable management is in the long-term interest of all riparian states.

Absent such frameworks, the trajectory is clear. Upstream infrastructures will multiply, downstream vulnerabilities will deepen and the space for cooperative solutions will narrow. The crisis along the Tigris today may well foreshadow similar conflicts on other rivers tomorrow.

What happens next along this ancient waterway will therefore resonate far beyond the Middle East. It is a test case for whether international society can adapt its institutions and norms to the realities of a warming, increasingly water‑stressed world—or whether geography and unilateral power will continue to dictate outcomes, regardless of the human and ecological cost.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) and why is it significant?

The Southeastern Anatolia Project, known as GAP, is one of the largest and most ambitious regional development initiatives ever undertaken by the Turkish government. Spanning roughly 10% of Turkey’s land area, the project involves the construction of 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric power plants along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Its primary objectives are to reduce Turkey’s dependence on imported energy, alleviate poverty in southeastern Anatolia, and provide a stable water supply for large-scale irrigation. By transforming arid lands into productive agricultural zones, GAP has turned the region into a major hub for high-value exports, particularly cotton.

How has the construction of the Ilısu Dam specifically affected Iraq?

The Ilısu Dam is particularly controversial because it sits directly on the Tigris River, which provides the vast majority of Iraq’s surface water. Since the dam began regulating and retaining water, Iraq has experienced a significant reduction in river flow, sometimes receiving only 30% to 40% of historical averages during dry seasons. This has led to a multi-layered crisis: a shortage of safe drinking water, the hospitalisation of thousands due to high salinity and pollution, and the forced abandonment of farmland. Furthermore, the reduction in freshwater has allowed salt water from the Persian Gulf to push further inland, devastating the delicate Mesopotamian marshes and the communities that depend on them.

Why is cotton cultivation in Turkey a point of contention for downstream nations?

While cotton is a highly lucrative export for Turkey, it is an exceptionally water-intensive crop. Producing just one kilogram of raw cotton can require up to 10,000 litres of water—significantly more than traditional cereal crops. As Turkey expanded its irrigation networks through the GAP project, it shifted agricultural focus toward cotton, which necessitates retaining and diverting massive volumes of water that would otherwise flow into Syria and Iraq. For downstream observers, this represents a prioritisation of industrial and economic growth in the upstream nation at the expense of basic water security and survival in the downstream nations.

What happened to the ancient city of Hasankeyf?

Hasankeyf was a settlement with a 10,000-year history, featuring thousands of man-made caves, Roman ruins, and medieval Islamic monuments. Despite its immense archaeological and cultural value, the city was located within the area designated for the Ilısu Dam’s reservoir. Although some prominent monuments were moved to higher ground through complex engineering projects, the vast majority of the ancient city, including unexcavated sites and the historic cave dwellings, was submerged when the reservoir was filled. This loss has been cited by international heritage organisations as a major cultural disaster, as an irreplaceable link to early human civilisation was destroyed in favour of hydroelectric and irrigation benefits.

Is there an international legal framework to resolve these water disputes?

Currently, there is no comprehensive, legally binding water-sharing treaty that governs the Tigris-Euphrates basin. Unlike other major international rivers that have established quotas and monitoring mechanisms, the Tigris and Euphrates operate in a legal vacuum. Turkey classifies these as “transboundary” rather than “international” rivers, arguing that it has sovereign rights over the water within its borders and no fixed legal obligation to release specific volumes to Iraq or Syria. This lack of a formal framework means that water management is often dictated by geographical advantage and political leverage rather than international law, leaving downstream countries highly vulnerable to upstream infrastructure decisions.